Our family knows little about why Abuela, my paternal grandmother from Silivri, a Turkish town on the outskirts of Istanbul, ended up crossing the sea and finding her way to Cuba. The story goes that her parents sent her to Havana to wed another Sephardic Jew, also from Silivri, but she took too long to arrive so he married someone else. Her only relative in Cuba, an uncle in Havana, took her in.

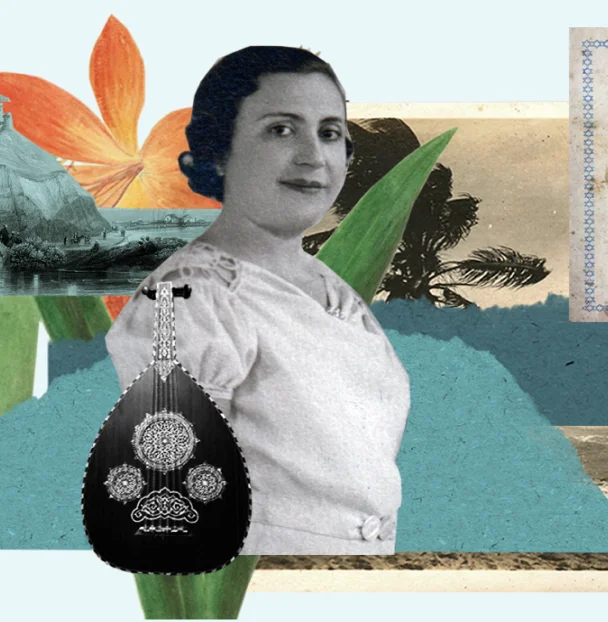

To pass the time, she sang sad Sephardic love songs and accompanied herself by strumming on the oud she’d brought from Turkey. That was how she attracted the man who would become my Abuelo, also from Silivri. He proposed after passing by and hearing her sing in Ladino about heartbreak. After marrying, they lived in a tenement in Old Havana that looked out at the sea. They had four children, the third my father, who says Abuela stopped playing the oud after becoming a wife and mother. Her oud hung from a nail on the wall in their apartment on Calle Oficios. She never sang again. Never saw her parents again.

Her story stayed with me over the years, leading me to ask questions about identity, mine and hers: What does it mean to be Jewish in Cuba, to be Sephardic, to be an exile in a family of exiles? I recently authored a novel for young readers, Across So Many Seas, inspired by the silences of Abuela’s story and the oud she once played. But before I could write it, I spent years studying the history and the present reality of the Jewish community in Cuba and the Sephardic presence within that community.

It is well known that conversos, descendants of Jews who converted to Catholicism in the years of the Inquisition, were part of Cuban society during the Spanish colonial period. But it wasn’t until after the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898, and the separation of church and state in 1902, that Jews could openly practice their religion. Sugar wealth and Havana’s transformation into a major port city turned Cuba into a prosperous country that attracted immigrants and investors. American Jewish expatriates of Ashkenazi background established businesses and laid the groundwork for a Jewish community on the island. Though totaling just about 1,000 people, the community founded the first Jewish cemetery in 1906 in Guanabacoa, on the outskirts of Havana, as well as the famed Moishe Pipik kosher restaurant in Havana.

Sephardic Jews started to arrive in large numbers in the early 1900s. A few came from Syria but almost all were from Turkey, many from the town of Silivri, like my Abuela and Abuelo. Early immigrants typically were men escaping compulsory service in the Turkish army. Later, immigrants more commonly traveled with their families, fleeing poverty and nationalist policies that arose after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, which threatened their ability to express their faith and enjoy their Sephardic heritage. In 1914, the Sephardic community in Havana established the Chevet Ahim synagogue (on Calle Inquisidor, no less). Ten years later, Rabbi Gershón Maya, from Silivri, founded the first Jewish day school in Cuba. An enclave formed, with a Sephardic radio program and stores selling kashkaval cheese for making borekas.

Fluent in Ladino, these Sephardic immigrants understood and spoke Spanish and as a result quickly integrated into Cuban society. While many lived in Havana, the community branched out to towns and cities in the eastern end of the island, the region known as Oriente, building synagogues in Sancti Spíritus, Camagüey, Guantánamo, and Santiago de Cuba. They felt a sense of belonging in Cuba; they’d found their Espanya in the tropics. This stood in contrast to the large numbers of Ashkenazim from Poland and other countries in Eastern Europe who mostly spoke Yiddish, struggled to learn Spanish and tended not to interact with non-Jewish Cubans.

Jews were immigrating to Cuba because the U.S. government had enacted a strict quota system in 1924 that made it nearly impossible for people from Eastern and Southern Europe to arrive at Ellis Island. As antisemitism and poverty increased in Europe, many Jews searched for a safe haven in Cuba. They had heard the island was so close to the U.S., you could swim there (something only Diana Nyad has accomplished). So many of the Jewish immigrants came from Poland that the Cuban term for a Jew, to this day, is polaco. While 15,000 Jews were permanent residents in Cuba before the 1959 revolution, many more passed through.

As the Ashkenazi community grew in Cuba on the eve of the Holocaust, Sephardim felt it even more essential to develop their communal institutions. Ashkenazi neighbors viewed Sephardic customs and traditions as exotic and “questionably Jewish.” The two communities, with different languages, foods, and cultural and liturgical traditions, stayed apart. When my parents, an Ashkenazi bride and Sephardic groom, married in Havana in 1956, the union was considered a kind of intermarriage. My mother’s family asked, “How could Albertico’s family be Jewish and not speak Yiddish?” But for my Sephardic family, the Ladino affinity with Spanish, Cuba’s native language, made the island feel quite Jewish.

I wish I knew more of the individual stories of the Sephardim — especially the women — who came to Cuba and built new lives in the tropics. I do know that my paternal grandparents barely eked out a living. Like many Sephardic men, in Havana and the provinces, Abuelo was a peddler, carrying blankets and shirts on his shoulders from house to house. He’d make my father come along with him, which he found humiliating. Abuelo worked only until noon and then would get together with other immigrant men from Silivri to play dominoes. Once he was given a package of meat by a customer and happily brought it home to Abuela. Though they were hungry, Abuela refused to accept the gift; she promptly tossed the meat off the balcony because it wasn’t kasher.

An enclave formed, with a Sephardic radio program and stores selling kashkaval cheese for making borekas. ”

Other Sephardim climbed the social ladder and became successful merchants. Grateful for their prosperity and confident they would stay on the island for generations to come, they began in 1957 to build the Centro Hebreo Sefardí, a synagogue with a seating capacity of over 700 people in the elegant neighborhood of El Vedado, far from the crowded winding streets of Old Havana. There was a competitive reason for locating the synagogue in El Vedado. The Ashkenazi community had just built a few blocks away El Patronato (Beth Shalom), a combined Jewish community center and massive sanctuary that proved Jews had found a home in Cuba.

Little did both communities know that the Cuban revolution in 1959 would bring Fidel Castro to power, that private enterprise, including peddling, would be outlawed, and that all religions would be suppressed in keeping with communist ideology. The Centro Hebreo Sefardí was completed in 1960. In that same year, Rabbi Nissim Gambach, a Sephardic rabbi in Cuba who originally was from Istanbul, published a Haggadah. The poignancy of the timing of this last Passover in Havana moves me deeply. It is sad to think how unaware Rabbi Gambach and others were of the mass Jewish exodus about to take place the following year. In April 1961, after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, Castro declared that the revolution would be communist and won the support of most Cubans. There would be no turning back to what the island once had been.

While a handful of Jews chose to stay and participate in the social experiment of the revolution, most did not. About 90% of the Jewish community fled in the early 1960s, both Sephardic and Ashkenazi. Their flight out was part of a wave of middle-class emigration that also included Cuban Catholics and Protestants. They all felt threatened by the nationalization of private property and the elimination of private enterprise, as well as by the pressure to give up individual ethnic and faith identities and be part of a unified Cuban nation fighting against imperialism. The literacy campaign in 1961 and the turn to public education for all Cubans would soon lead to parochial schools being shut down. Families that sent their children to Catholic, Protestant or Jewish schools in Cuba didn’t want their children to receive an atheist education that glorified the revolution. There were also fears that children would be sent to the Soviet Union for communist indoctrination.

Many Sephardic Cubans fled to New York, then Miami, where they founded Temple Moses in North Miami Beach. But leaving behind their plush new synagogue in Havana, with its ark that held nine Torahs from Turkey, was experienced as a tragedy, as the loss of a kerida, a beloved. For the Sephardic community, their departure felt like another expulsion. Indeed, a plaque at the entrance to Temple Moses speaks of the synagogue being founded in 1968 by “Cuban Jews forced into exile” and states, “We will never forget what we left behind on the island of Cuba.” While Sephardic Cubans weren’t targeted by the revolution, the historical memory of exile sat heavily on their shoulders, and they recognized they were part of multiple diasporas that had taken place generation upon generation.

For those Cubans who weren’t Jewish and settled in Miami in the 1960s, when a vibrant American Jewish community already existed there, the notion they developed of themselves as exiles was borrowed from the Jews. As it became clear the U.S. government was not going to depose Castro, and those who left wouldn’t be returning to Cuba any time soon, Cubans took on the position of being exiles and began to say “next year in Cuba,” echoing “next year in Jerusalem.”

Nearly all who left in the 1960s, including my parents and grandparents, chose never to visit Cuba again. They preferred to hold on to the Cuba of their memories. But being a cultural anthropologist, I felt compelled to see the island with my own eyes. I started traveling to Cuba in the 1990s and continued going back and forth for the next 30 years. I witnessed the spiritual renaissance that took place after the fall of the Soviet Union, which had subsidized the Cuban revolutionary project. I also watched as the economic downturn, known as “the special period,” led to extreme austerity measures. G-d was allowed back on the island as the government removed restrictions on religious observance and welcomed humanitarian religious groups from the United States. The Jewish community in Cuba, with support from the Joint Distribution Committee and other American Jewish organizations, came back to life. The synagogues on the island, built by those who left in the 1960s, were restored and welcomed a new community made up almost entirely of Jews of mixed ethnic, religious and racial backgrounds.

Leaving behind their plush new synagogue in Havana, with its ark that held nine Torahs from Turkey, was experienced as a tragedy, as the loss of a kerida, a beloved. ”

I wanted to meet the Sephardic Jews who stayed in Cuba after the revolution as well as their descendants, about 1,000 people at the time, and my journey led me to make a documentary film, Adio Kerida. One of the young people in the film is Danayda, whose father, José Levy, the leader of the revitalized Sephardic community at that time, was teaching her to chant Torah for her bat mitzvah. Her mother was a Black Cuban Jehovah’s Witness and I was struck at the ease with which Danayda embraced her hybrid identity and how strongly she felt about Jewishness being a core part of herself. Since the making of the film, she made aliyah and became a fluent Hebrew speaker in Israel, where she often was mistaken for Bedouin because of her skin color but always spoke Spanish to her two daughters to keep alive the memory of Cuba. After returning to Cuba last summer, the family decided to stay indefinitely. She is between Cuba and Israel now, her Sephardic identity a bridge between the two.

I also wove into the film the story of Albertico Behar (no relation to my father), whose revolutionary Sephardic father had rejected religion throughout his life. But when he was on his deathbed, he asked his son to bury him in the Sephardic Jewish cemetery (next to the first Jewish cemetery built in Guanabacoa by Ashkenazim from the U.S.). Albertico never had been to the cemetery and knew nothing of Jewish death rituals. At the cemetery, he learned he needed to say the Kaddish, but Albertico had to admit he didn’t know what a Kaddish was. A Jewish elder recited the words and asked him to repeat them, but he refused to do so without knowing their meaning. Later, he regretted not having offered his father a proper goodbye. By then, the Joint Distribution Committee was assisting with the revitalization of Jewish life in Cuba, and Albertico decided to study Torah. He learned to chant so well that he soon was leading Shabbat services and preparing children for their bar and bat mitzvahs.

Throughout most of the last 30 years, it has been moving for me to witness Jews on the island coming together and forming a vibrant, diverse community. To this day, they run their own religious services and offer Sunday school classes, not only in Havana but in the provincial cities, too. I documented this revitalization in my book, An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba, collecting the stories of Jews who were finding their way back to their heritage or joyfully becoming Jewish after choosing to undergo a conversion process.

But now, sadly, the community is waning. Many have left Cuba for Israel and the U.S., and the crisis of the pandemic and the decline of tourism and humanitarian religious travel to the island have led to dwindling resources. Synagogues can barely keep the lights on. They open for holiday celebrations — most recently, a lively Hanukkah party with Cuban and Israeli dancing — but no longer offer weekly services and the Shabbat meals essential to many in the community. Still, there is hope that, after a long hiatus, American Jewish missions are revving up and will start to return and much-needed aid will pour in again. This will help the elders who barely survive on pensions. But the Jewish youth in the community mostly dream of a future elsewhere.

Some fear a day will come when there will be synagogues in Cuba and no one to attend them.

Fortunately, that day hasn’t arrived yet. There are more than enough Jews to form a minyan, and those who remain feel a strong sense of pride and deep connection to their heritage and to the global Jewish community. There are also young entrepreneurs whose feet are firmly planted in Cuba and are working to draw attention to how the Jewish presence fits into the rich diversity of Cuban culture. For example, Abel Hernández Eskenazi, a 23-year-old engineer, has used his technological skills to create an app on Google Play, “Judíos en la Historia de Cuba,” that offers information on the 500-year history of the Jewish presence on the island. He also has begun offering tour guide services through a start-up, “Havana Jewish Tour.”

I want to imagine that there always will be Jewish people living on the island where I was born. I often try to envision Abuela playing the oud and singing Sephardic songs of heartbreak after arriving alone to the shores of an island so far from Silivri. It was this sense of loss, this goodbye of hers, I carried with me on my many visits to Cuba. Everywhere I went I heard echoes of her voice, echoes of her oud, echoes of an Espanya in the tropics where all the Sephardim expected to stay forever.