Sephardim have guaranteed transmission of cultural information through a system that involves verbal and non-verbal knowledge transfer. I have named this system of multidirectional transmission: “Sontinuity: The Tree and the Web.”

As a Western Sephardi intellectual of Moroccan, Italian and British ancestry, for decades I have undertaken serious study in analyzing the unspoken patterns embedded within Sephardi history and music. After receiving my doctorate from the Sorbonne focusing on Judeo-Spanish music and identity, I moved to the United Kingdom for a position at the University of Cambridge, where I currently am a senior research associate. During my fieldwork in Morocco, I started KHOYA: Jewish Morocco Sound Archive, recording thousands of hours of Jewish oral histories and soundscapes.

In this article, I will explain the process of Sephardi transmission through a linear explanation (Tree) and a sensorial metaphoric explanation (Web) so readers can experience the need, power and interlacing of both to achieve long-term cultural transfer and community resilience by employing the very same system used traditionally.

The Tree explains the manners in which Sephardim established lineages and networks of knowledge to ensure a foolproof system for transmission after the expulsion. Using a complex system that deploys multidirectional influence between formal institutions, informal networks, family, gendered spaces, life cycle events, and the yearly cycle of festivals, the Sephardi diaspora has ensured its continuity through challenges such as multilingualism, repeated migrations, forced conversions, assimilation, and genocide. When we understand Sephardi resilience through this system of transmission, it becomes clear that every member of the community plays an important role in maintaining the ecosystem so that future generations will access ancestral knowledge.

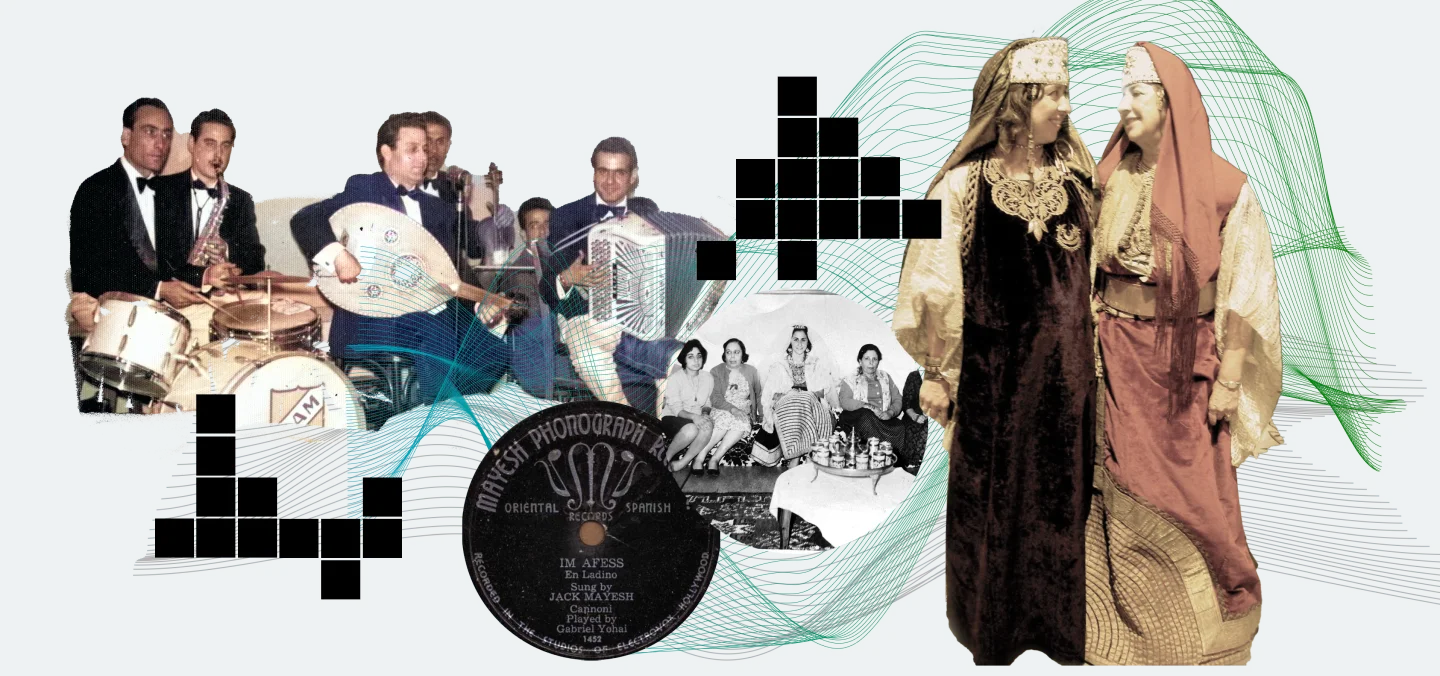

The Web features a cohesive series of three stories, each accompanied by images and musical clips. I invite readers to absorb the complementary story elements together, and therefore to full effect.

The Tree: A linear explanation

After the cataclysm of the 1492 expulsion and dispersion — which was followed by a slow reconstitution of communities around the Mediterranean, Western Europe, and eventually into the Fertile Crescent, Africa and the Americas — one could wonder how Sephardim could have codified information to ensure transmission of traditions in such a wide multilingual geography. Is it even possible to maintain cultural resilience when faced with such trauma?

My academic study over the last 20 years has focused on establishing how Sephardim have employed multidirectional methods of transmissibility of their core cultural information over the long durée — in other words, how the community developed mechanisms to ensure transmission and resilience after traumatic rupture.

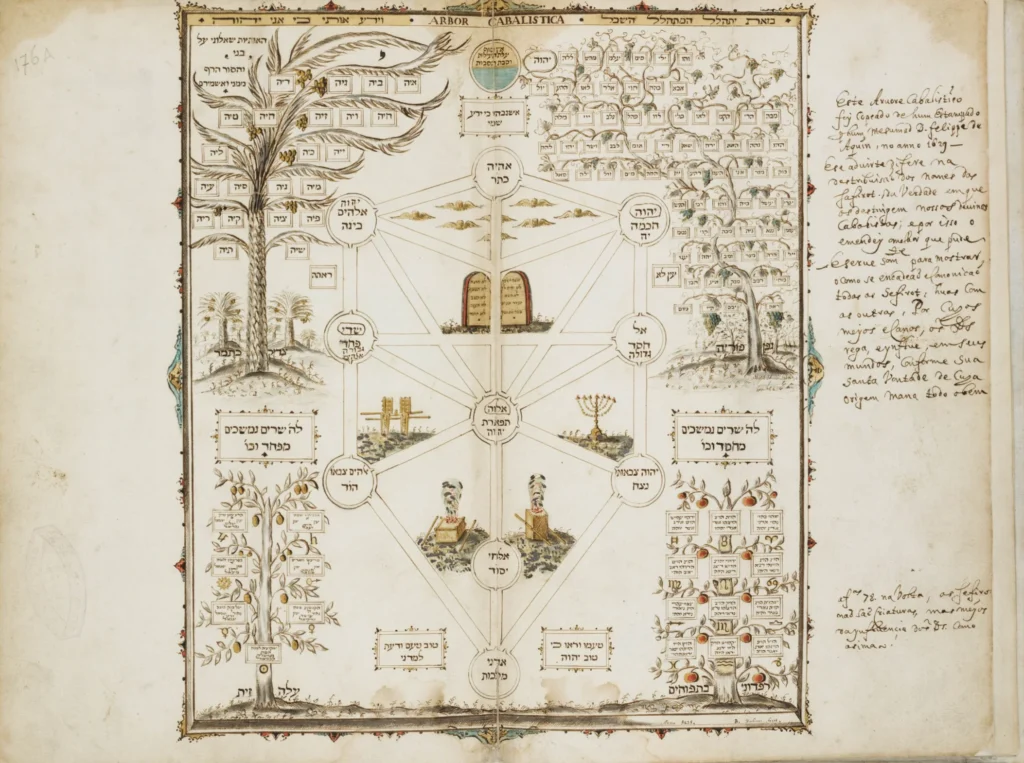

I discovered that Sephardim used two parallel channels for transmission after the expulsion. They are what I call, simply put, the tree and the web. The tree is a manner of creating genealogies of transmission, family trees of sound and thought that were passed on unidirectionally through belief, texts and melodies. Genealogical theories of being were crafted through formal arborescent (tree-like) hierarchical shapes, which plot a point, fix an order.

By contrast, the web is a dispersed model, akin to a non-hierarchical network (rhizome), and potentially could lead to loss of tradition because of its lack of center and clear direction. A rhizome can be connected to anything other, without maintaining linear connections to the direct past. Because multiplicities are rhizomatic, “they expose arborescent multiplicities for what they are,” according to the French philosophical theory of Deleuze and Guattari.

In this system, the synagogue, the study hall and traditionally male liturgical spaces served as the tree, whereas the home, communal gatherings and traditional spaces of primarily feminine oral traditions function as the web. This, however, does not imply a zero-sum gender binary as women can engage in arborescent dynamics and transmission, and men in rhizomatic networked connections. The blurring between the systems is exactly when transmission occurs between tree and web. These are some of the richest and most fruitful interactions in cementing knowledge across generations.

Sephardi women’s repertoires integrated communal knowledge of Arabic/Greek/Turkish/Balkan or Hebrew and Judeo-Spanish texts into the understandings behind the narratives that they were exhorted to sing, and often not speak — or that people heard from female voices as proverbs but also read in rabbinic texts. This web-like transmission shows that the production of voice and its listening was a choice context for the transportation of Sephardi knowledge between gendered sonic spaces, a methodology of “sontinuity.”

Thus, a voice could send a message through the generations in an arborescent manner (the tree) or embody the weblike connection that transmitted regardless of authorship through women’s repertoires. Their vocalities symbolized fertile lands and the relationship to rain, seed, agriculture, and prayer — a transmission based on connection and shared roots more than focused directionality.

Jewish men’s melodic transmission in the Mediterranean was closely allied with the non-Jewish population’s music, using the rhythmic and musical modes of the majority’s classical or popular repertoire — Arabo-Andalusian music, Greek rebetiko or Turkish maqam — possibly to align themselves with the majority culture’s soundscape. Still today, synagogues function as hubs for the transmission of melodies, poetry and belief, together with gestural aspects that demonstrate belonging (or not). Synagogues function hierarchically and follow the arborescent model of evolutionary developmental patterns that follow genealogies of physical, intellectual and spiritual lineages that connect to world Judaism.

In contrast, women’s repertoires often are local and function as a nodal core within a large rhizomic structure of Sephardi diasporic transmission.

This double strategy explains the success in Sephardi “sontinuity”: sonic embedding of belief, ritual and belonging in such a wide and diverse diaspora.

Lastly, the strong presence of feminine musical transmission in Sephardi communities may be related to the minority status of the community. Through repeated performance of certain repertoires, even extremely simple ones, music then becomes a “refrain” for demarcating the space around land, community and self. The sonic — through voice, song, speech, or chant — creates a communal self to recenter belief systems and cultural objects as central hierarchies that establish agency. The refrain of music demarcates the “we” that diasporic communities fight to establish and maintain. By teaching and making music or using proverbs that are perceived as group-specific, a sonic boundary is maintained demarcating insider-status. Once the group-specific sonic refrain is established, other sounds can be introduced and they will carry the original core knowledge of the group.

The Web: A sensorial metaphoric explanation

Once upon a time there was a grove of trees. Even though the trees could not move, thus giving the impression of being separate from each other, they worked together with all the other trees in the vicinity. The trees had a system where they would communicate with each other underground with tendrils that brushed up against others without knowing who owned each tendril. The key to their success was that they gave from their nourishment and knowledge without knowing who the recipient was because the very action of disentangled giving propelled the movement of the system in a much more powerful manner.

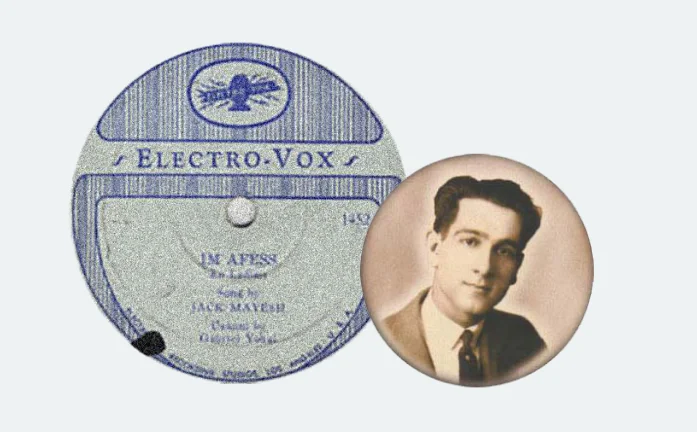

Im Afess (En Ladino), sung by Jack Mayesh, 1942

Turkish Ladino liturgy, recorded in Los Angeles. From the collection of Joel Bresler

Lyric excerpt:

“El pueblo Israel no será nunca exterminado, un amor del patriarca Rav el venerado.”

(“The people of Israel never will be exterminated, they are beloved of the venerated Rav patriarch.”)

The exchange between the tendrils underground and the sap of the trees above was not always simultaneous or obviously discernible. But when one part of the system moved, the other part felt a wisp of a seeming shift. The reverberations were felt within the different parts in a tangible manner when nourishment of one distant section of the grove occurred. It functioned as a deeply nuanced pressing into the sensitive membranes of the inner-self, or an echo of a reverberation. When the trees were nourished by the sun or the root tendrils by the rain, the different parts of the interconnected system focused exclusively on themselves, gently absorbing directly, knowing that the sharing of gathered resources would happen afterward.

Rosablanca, sung by Julia Bengio, February 9, 2008

Recorded in Tangier by Vanessa Paloma Elbaz. KHOYA: Jewish Morocco Sound Archive

Lyric excerpt:

“En la habitación y le acunaba y ella cantándole Rosablanca Rosabla … y ella se movía Rosablanca y yo iba y venía y la escucho — hasta mi hija chica se acuerda que mi tía le cantaba la Rosablanca, y después me escuchaba a mí Rosablanca y el nuevo amor.”

(“In the room she was cradling her and singing, Rosablanca, Rosabla … and she was moving Rosablanca and I was coming and going and listened — even my youngest daughter remembers that my aunt sang her the Rosablanca and later she heard me Rosablanca and new love.”)

Sometimes a tree in the forest became ill, was cut down or burned through an act of nature or human aggression. The anguish of another’s suffering was felt by the whole grove and the repercussions from this pain were experienced throughout the system in varying manners. Resources from all over the grove were deployed quickly to try to nourish and heal the suffering tree. When an individual or a section of the grove died, its knowledge did not disappear because it had been disbursing it through the collective for years prior to its disappearance. After a period of rest and recuperation, or what could appear to be dormancy, shoots would emerge and birds, insects, mosses, flowers, and worms would participate in redistributing the disappeared tree’s resources. When a tree or grove in a distant geography, placement and symbiotic system show elements drawn from the former disappeared tree’s knowledge, we have confirmation that the various strategies for transmission have secured continuity and demonstrated resiliency. The transmission of its knowledge was assured.

YouTube direct links