Facing the Minister of Culture, I stand on my toes to support myself on the overly high lectern and reach the microphone stretched out toward me. The directors of France’s museums face me, and the entire Commission for the Restitution of Looted Objects waits with bated breath.

These will be my first and last words to the French eminences before my departure from the country where I was born and raised, having lived in the same working-class Paris neighborhood my entire life. I have come to the painful realization that despite my multicultural and political activism as a Jew — or perhaps because of it — I no longer can remain in France.

My dress is sewn with gold thread, similar to the small liturgical object that has been returned to my family and is the subject of this official restitution ceremony. To the left of the podium, the immense and unique portrait of my great-grandfather, dressed as Hamlet, perhaps on the stage of the Algiers Opera. My whole life’s journey, 33 years of existence, are concentrated in this suspended moment of justice and reparation.

I was born into a rather assimilated, economically modest, socialist and feminist family of Jewish intellectuals: the daughter of an Algerian Jewish father forced to flee his country in 1968, and a Polish Jewish mother whose parents survived the Shoah before finally finding political refuge in France. I knew from a very young age, and I still know today, that Jews must have a voice in national debates about decolonialization — whether in Algeria or France. I now know I no longer can remain silent, no longer hide myself in the face of humiliation and fear while my community is fleeing from a national, shameful silence. I also know that I want to become a mother and raise children who do not fear being themselves in public, who will never be ashamed of their tradition, history, language and culture. It has been painful to admit it, but this is increasingly impossible in France.

Standing before the assembly, I have only a few minutes to tell the story of all the intertwined lives that have led to today, to pay tribute to those who disappeared, to trace a thread between colonization in Algeria, the Shoah, French collaboration, the destruction of Algerian Jewry, the Algerian War of Independence, exile, and the contemporary rise of antisemitism in France. A heavy responsibility for a single person. I have only a few minutes to go back up the chain of generations, to join the ranks of the living and to mark the end of a first existence in France. This separation must be made with height and grace, the imperative of reparation and forgiveness must prevail, despite the tragedy that underlies the situation.

* * *

The small artifact, our family heirloom, is a tefillin bag dating from 1888 and found in a shed in Germany after the war by the Jewish Restitution Successor Organization, whose aim was to recover property that the Nazis looted. This bar mitzvah bag, which was used in a celebration in Algiers, belonged to Élie Léon Lévi-Valensin, my great-grandfather, who died destitute in Algiers in 1945. It is a looted object that has remained in the collections of the Museum of Art and History of Judaism in Paris (mahJ) since 1951, one among the 100 looted objects it holds, and the only one from North Africa.

In many ways, this bag is making history. It is the first liturgical object ever to be returned to its owners. It is the first object to be returned from Islamic lands. It is the first object to be returned that has no monetary value. It is a proof of the Holocaust in North Africa. Its words, embroidered with gold thread, contain a hint of Ladino, a trace of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain.

And a name, the name of a man, is finally pronounced and recognized here: Élie Léon Lévi-Valensin.

An Algerian Jew, of French nationality, an opera singer and the artistic director of the Kursaal of Algiers (the capital’s comic opera house) whose grave remains in the Saint-Eugène cemetery of Algiers in the same vault as his parents. Under French colonial rule in the 1920s, he was the first to program a concert of classical Algerian Arabo-Andalusian music in a public theater in Algiers, with an orchestra made up of Jewish and Muslim musicians. This was a seminal political act that paved the way for Algerian theater in Arabic, led by Mahieddine Bachtarzi and his troupe, which also was made up of Jewish and Muslim actors.

A contemporary of the Edmond Nathan Yafil, a Jewish musician, composer and conductor who gained notoriety. In contrast, this man, this artist, my great-grandpa, has been forgotten by history, with the fragments of his archives destroyed or confiscated by the Algerian authorities and the French colonial archives. All that remains is this black-and-white picture in the costume of Hamlet, which now sits in this Parisian townhouse, above the artistic columns of Daniel Buren that dot the courtyard of the Palais Royal.

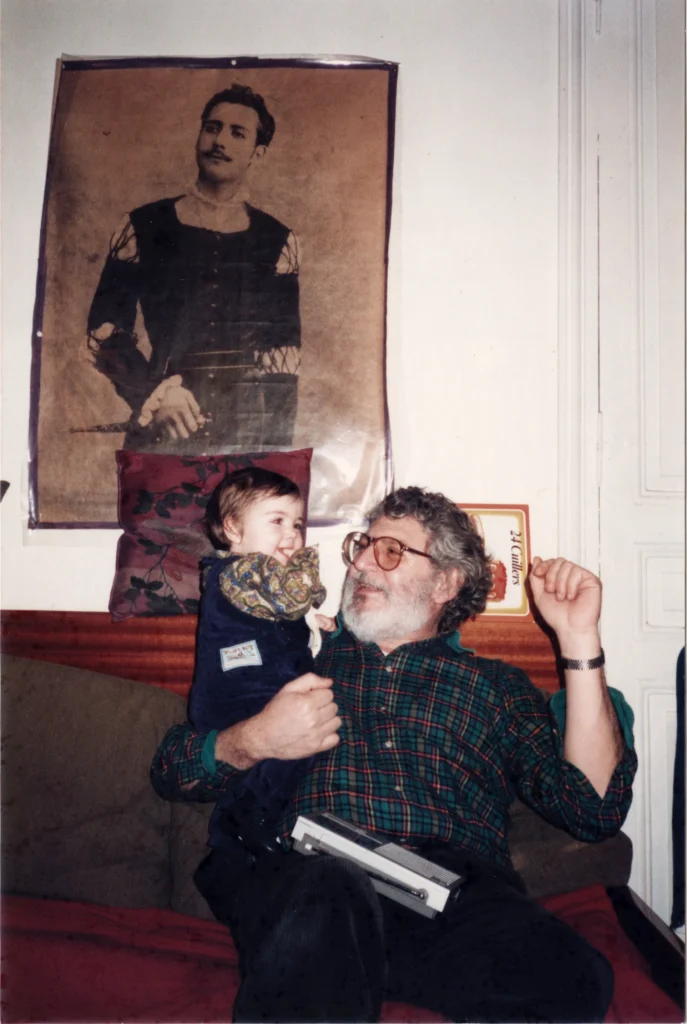

A young Miléna Kartowski-Aïach is held by her beaming father, Pierre Aïach, in front of the treasured portrait of her great-grandfather, Élie Léon Lévi-Valensin

Photo courtesy of Miléna Kartowski-Aïach

I tell the assembly, in a text stitched from memory, how I found the pouch during the final hours of the exhibition on the Jews of Algeria at the mahJ on January 27, 2013, or perhaps how this prayer bag came to find me in order to entrust me with a mission. I recount the entire investigation, piecing together the fragments of my great-grandfather’s history and unraveling the mystery of the object’s spoliation. I recount and pay tribute to the friend from Algiers, a righteous among the living, who devotes his life and risks it, in order to write the history of the Jewish musicians in Algeria, and has given his whole heart to tracing Élie Léon’s path through the few archives that can be consulted in Algeria.

I tell the story of my Sephardi and Judeo-Berber father, Pierre Aïach, grandson of Élie Léon. Born in 1935 in the colonial French capital of Algiers, my father was uprooted from his Judaism, a victim as a child of the Vichy laws. Despite supporting Algerian independence as an adult, he had no choice but to flee in July 1968 at the age of 33 (which also happens to be my age on this fateful day) because of antisemitism among the Algiers faculty where he taught economics and the country’s refusal to include Jews or other minorities in its increasingly monolithic, pan-Arabic society. My father was one of the last Jews in Algeria and certainly a direct descendant of Yehouda Ayache from Medea, who was the Chief Rabbi of Algeria for more than 25 years in the middle of the 18th century.

In front of the Chief Rabbi of France, my mother and my friends, I tell how this story led me to open my eyes to the country where I was born, and where violence against Jews is intimately contained in the earth beneath our feet. At my public school, I learned about the French Resistance, but not so much about the French collaboration. I know that my father as a child was expelled from school due to Vichy laws and that my grandfather, Edmond Aïach, was banned from practicing his profession. I know that members of our family were in forced labor and internment camps in southern Algeria, and that Operation Torch which took place on November 8, 1942, and enabled the Allies to land in North Africa and save the Jews from certain deportation, was led by a group of young Resistance fighters, mostly Jewish, headed by my family member José Aboulker.

I know all this because I’ve been told about it, and I’ve tried to understand history, my history, beyond the official French narrative. At this hour, in the face of those in power, I demand justice for the victims and recognition for the forgotten heroes. I call on the French state and the Algerian government to open their archives and return to the Jews their unjustly confiscated history, which is 2,000 years old.

Then, in front of my own rabbi and the country where I was born, I announce that I am leaving France and will make my aliyah in five days. I won’t be leaving the tefillin bag to the Jewish museum in Paris, which is asking for it. I refuse to do this because it’s the last and ultimate fragment of a Jewish history that now must be told by its heirs, who have been deprived of their memory until now. I know that this restitution ceremony is an important link in the recognition of the Jewish history of Algeria and the Holocaust in North Africa. It is also an important moment in the recognition of the contemporary antisemitism striking the Jews of France, who increasingly are being forced to leave. So I’ll be leaving for Israel with the empty tefillin bag in my rucksack and a mission to fill it with my own prayers.

* * *

Now that history has been retraced. Now that the call for justice and reparation has been made. Now that the boxes have been packed and my whole first slice of life lies in a warehouse along with hundreds of other containers in transit to Israel. Now that the tree of French existence has been uprooted and all the tears of a human being torn apart have been shed. Now that I’m leaving my parents, my world, my life here. Now, yes now, these are the last words I wish to share with France. All that is needed at this moment, to respond to the forces and tragedies of history and to soothe my heart, is a prayer, a last Jewish prayer.

I choose the Kedushat Keter. When recited, all the believers stand on tiptoe, like angels, facing G-d in order to touch the heights and make heard the sanctification of the Name. I choose the Kedushah, central to Jewish prayer, because it is a call to rediscover the royalty of our humanness on earth and restore broken lives.

Aren’t we, in this total movement of prayer, acknowledging that the time has come for humanity to gird itself with this divine crown in order to face the world before it, and thus be worthy of the history we will write on earth? I decide to pray in the Gibraltar liturgy that originated in Spain, and which is a direct link today since a large part of the Algerian liturgical rite originated in Spain.

I place both feet on the ground, anchored as deeply as possible. I inhale, thanking the elders who have secretly led me here. In my inner preparation, I ask for reparation (tikkun) for the Jewish people and the right to life. With closed eyes, in a tenuous silence, I pronounce the first word, keter (the crown), which I draw out and vibrate as long as the exiles of the Jewish people. I am one voice and a thousand voices. The voice of a Jewish woman, unveiled here, praying in the sacred language of her people, in front of the Chief Rabbi of France, lowering his eyes to escape the moment. I waver but don’t stop, clinging to the lectern. The force of the moment continues to carry me on, despite the fear inside me.

I won’t be leaving the tefillin bag to the Jewish museum in Paris, which is asking for it. I refuse to do this because it’s the last and ultimate fragment of a Jewish history that now must be told by its heirs, who have been deprived of their memory until now. ”

Will I be stopped? Will a man stand up trying to silence me? Will the Minister of Culture take to the stage and invoke French secularism so that I should end this prayer from the heights? Will I succeed in ending my French-Jewish silence here during this unique and ultimate prayer? I pray, without saying the name of G-d, whose mysterious forces are deeply present at this moment.

Everything appears to be shattered and broken, while at the same time unifying toward a possibly repaired existence. The Shoah, the survivor grandparents from Poland, the father torn from Algeria, the wound of antisemitism lived in the flesh. From the shores of mourning and the fields of ruin, the Kedushah, like a caress, becomes consolation. It is the grace deposited in this fleeting, eternal moment that enables us to tear ourselves away from the land of serfdom and cross the sea to a new existence.

Tears turn to prayer, enveloping the congregation until reaching the heart. The worst, painstakingly concealed, and the most beautiful come together in this moment of reparation, when, through this small returned object, the French state asks forgiveness and acknowledges that it has betrayed its own citizens. During these few minutes of prayer, the chanted words attempt to open up a territory of hope that is specific to forgiveness and reparation.

As my voice vibrates, naked, unveiled and revealing the majesty of a Jewish liturgy that no longer has its title of nobility in Europe, I summon my strength and assert my intention. Through this tear-prayer, which bears witness to and heralds a radical change in our existence, I wish to alert the world to the fate of my people in France and call for their protection. I hope at this moment that the world will awaken and restore its dignified humanity. I wish that the silenced voices could reveal themselves, especially the voices of the mute women, and thus bring all the beauty and restorative power necessary around them. I wish to leave the ruins inherited on this sacred vibration, choosing to embrace a human existence at last full and restored, and to give a ground to all the broken generations which I carry within.

I wish to give my prayer a land so that life, one day, may grow there.