In June 1989, my father, mother, sister and I stood together at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City and watched anxiously as a United States Customs and Protection officer, hole punch in hand, sealed our fate. We had just arrived in the U.S. after escaping post-revolutionary Iran.

“I want you to know this means that we can’t go back,” my father informed my mother in their native Persian.

“I know,” my mother responded solemnly.

My father showed my mother her Iranian passport, inscribed with the words “Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran” on the front cover, written in Persian, French and English. “Then we’re going to renounce our citizenship,” he said.

“I know!” my mother yelled back in saddened shock, but equally furious. “I need time to cope with this. For now, just stop waving that picture around!”

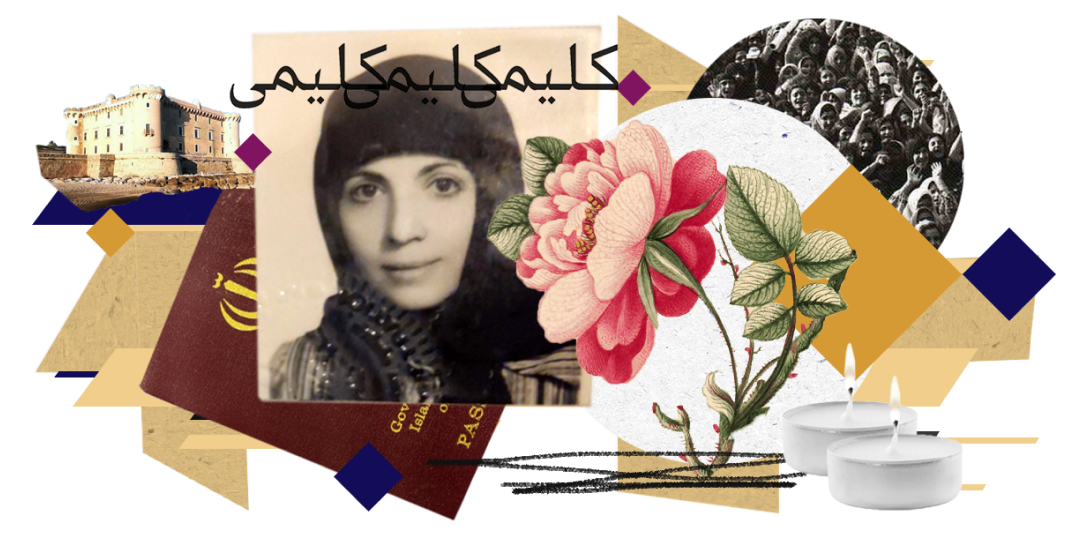

In her official Iranian passport photo from 1988, she looked sullen, if not downright miserable. Her luscious black hair was nowhere to be found, tucked beneath her mandatory hijab (the Islamic head covering for women). She looked nothing like the young glamour queen she had resembled just one decade ago, before the 1979 Islamic revolution turned Iran into a fanatic theocracy.

My sister and I huddled together next to our mother. We sympathized with her over the solemn passport photo but still did not fully understand why our mother felt so vulnerable and exposed at the thought of it, or why she held her Iranian passport in such disdain. And then I began to feel scared, wondering whether in the passport my mother had been identified falsely as a spy. Or worse, an enemy of the state.

After a few seconds, my mother shook her head, then blurted out an expletive to describe the regime bureaucrats who had insisted on typing Kalimeh next to her name on that passport. At that moment, my sister and I understood. That single word, Kalimeh, held a world of antisemitic meanings because it meant “Jew” in Persian. And it could not be removed.

“I did everything to try to get those people at the passport office to remove it,” my mother complained to my father. Decades later, she casually reflected on the incident: “I’ll have you know that the Americans never wrote ‘Jew’ next to my name when I got my passport for the U.S.,” she told me, as if identifying one’s religion on such a vital form of identification was standard practice worldwide and the Americans were kind enough to abstain from such behavior.

“If you need to punch a hole in the Iranian passports to revoke them,” my father told the customs official in his best English, “please punch a hole in mine.” Then, seeing the pain and fear in the faces of his wife and young daughters, my father hugged my mother and tried to lighten the mood, suggesting that the official not do the same for my mother. “My kids and I may want to send my wife back to Iran one day,” he said dryly.

My sister and I (and the official) nearly burst with giggles. It felt good to laugh again after the trauma we had endured in escaping Iran. Even my mother cracked a smile, something we had not seen in months. The customs agent promptly punched a hole in the corner of my father’s passport, thus making it official: There was no returning home. That hole punched in my father’s passport also meant my mother, my sister and I were prohibited from returning to Iran.

It was strange to see those passports, once the most official reminders that we were Iranian citizens, now effectively defunct. My photo and that of my sister’s were in our mother’s passport as well. We looked even more miserable than our mother because we were little Jewish girls in mandatory Islamic headscarves.

We joined the exodus of Jews who would never return to Iran; a thread in a communal tapestry that, before the revolution, was over 100,000, but today has dwindled to between 5,000 and 8,000. That day, we effectively renounced our Iranian citizenship so that we could be redeemed in America. And there we were, with the 21st century not long approaching, citizens of nowhere.

Through the magnanimous help of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (now known as HIAS), we arrived as protected refugees in Ladispoli, Italy, where we stayed for nearly nine months before transiting to the United States. Back in Iran, my father had worked for decades to finally achieve the one milestone that had eluded our family for centuries: financial security. We enjoyed a home, a beautiful car, and even more beautiful dresses and shoes for my mother, my sister and me. Those dresses, though, were always hidden in public when we wore our manteaux, or mandatory cloaks, that needed to be long enough to cover our arms, upper bodies and posteriors. I, for one, feared the brutality of Iran’s dreaded “Modesty Police” more than I feared the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps or even Ayatollah Khomeini himself.

The customs agent promptly punched a hole in the corner of my father’s passport, thus making it official: There was no returning home. ”

Overnight, we had descended from riches to rags. When we arrived in Italy, our first order of business was to scour the streets for mattresses. We finally found a used mattress on a street corner, which we dragged into an apartment HIAS had secured for us. That night, my older sister and I slept on that dirty mattress while our mother and father slept on the floor. The previous night, my father had locked the doors of our magnificent three-story home in Tehran, entered his large chemical adhesives factory for the last time, and sold his cherry red Camaro for an unjustly low price.

We shared that two-bedroom apartment in Ladispoli with a Russian Jewish family that HIAS had rescued from the former Soviet Union. As I lay on that uncovered mattress and listened to the Russian children argue in the next room, I thought about my own comfortable bed, and our home, back in Iran. It would be years before I would fully understand the painful scope of what my family sacrificed to secure freedom in the West.

We attempted to enjoy Italy, to the degree that traumatized, penniless refugees could enjoy the lovely country, but I knew I wasn’t Italian despite how many new Italian words I learned from the vendors at the local bazaars. In Italy, I was still perceived as a foreigner — an Iranian — at least on paper, because my passport had yet to be made invalid. That also was how I viewed myself.

But once I ceased being an Iranian citizen upon arriving in the U.S, I struggled to identify who I was. I worried that I was no longer legally Iranian, and I certainly wasn’t legally American (I arrived in the U.S. at 7 years old, and it would be another nine years before I received citizenship). One day, in second grade, my parents pulled me out of class so that I could obtain my Green Card. “Am I American now?” I asked my parents on the car ride home. “No,” my mother responded, “But don’t worry, even if you’re not, they can’t send you back to Iran. We’re protected refugees, at least.”

To celebrate our new Green Cards, we engaged in what we assumed to be an American rite of passage: Promptly identifying the nearest McDonald’s and calculating exactly how many chicken nuggets we could share between the four of us to save as much money as possible. There I was, an 8-year-old foreign national with a heart full of hope and a Happy Meal.

I wasn’t American (yet), and I wasn’t technically Iranian anymore. Still, I knew I had to be something.

In those early years in Los Angeles in the 1990s, I observed my family’s behaviors and rituals carefully. We were still Iranian, only speaking Persian at home, mostly shopping at Persian supermarkets, and using the Persian Yellow Pages (yes, such a resource still exists). We celebrated Nowruz (Persian New Year) and saw our Iranian refugee relatives every week for sumptuous Shabbat dinners at home.

Yet we were also growing more American by the day. Each October, my sister and I begged our parents for Halloween costumes. Each December, we begged for eight nights of presents during Hanukkah, mimicking our American Jewish friends. For the record, my parents promptly rejected both the Halloween and Hanukkah requests. My sister and I learned English and American culture at an astronomically faster rate than our parents, especially our mother, who didn’t know the difference between Bugs Bunny and Bart Simpson.

But there was something else. I began to wonder about how those in power identified us.

The previous night, my father had locked the doors of our magnificent three-story home in Tehran, entered his large chemical adhesives factory for the last time, and sold his cherry red Camaro for an unjustly low price. ”

As a child, I asked myself whether the regime back in Iran considered my family and me truly Iranian. Despite 2,700 years of continuous Jewish presence in Persia/Iran, I strongly suspected that the regime considered us as outsiders, hence the word Kalimeh on my mother’s passport. I then asked myself what the U.S. government, in all of its kindness, considered us when it allowed us to enter this country in freedom and protection. I didn’t believe the Americans offered us refuge because we were Iranian; there must have been something else.

And then, one Friday evening in third grade, as I observed the faces and rituals of my family and a dozen aunts, uncles and cousins at our apartment for Shabbat dinner, I understood. The table was set with mouth-watering Persian stews, rice and meats. We all conversed in Persian, especially when it was time to argue over who would be entitled to the first coveted helping of Persian fried rice (tadig). In the background, the distinctly American phenomenon of “TGIF” Friday-night television programming displayed a scene from “Full House.” We understood that we had barely anything in common with the fictional Tanner family that lived in a large Victorian home in San Francisco, but in its own way, each Shabbat, our small apartment magically expanded into a lively, crowded full house of its own.

My mother instructed my sister to prepare a homemade batch of Thousand Island salad dressing, another uniquely American concoction that my mother had tasted once, enjoyed and decided to replicate at home, using only tomato paste and mayonnaise. My sister objected; she didn’t want to miss a moment of “Full House.”

We were loud and alive, cackling and laughing. Someone asked whether the Los Angeles riots, which had occurred months earlier, would ever happen again. A cousin inched his fork suspiciously closer to the crispy tadig. My aunt demanded that the television volume be turned up because she was enamored with the Uncle Jesse character from “Full House.” This was why we had escaped Iran: to be wholly (and loudly) free. Seemingly nothing could have quieted us down.

And then, my mother entered the dining room, holding two Shabbat candles and a box of matches. I followed behind, holding a bottle of Manischewitz wine and a bag of fluffy pita bread.

The candles were scented tealights we had purchased at the local drug store, not the long and elegant taper candles often seen in children’s books featuring Ashkenazi families. The bread was a far cry from the challah some of the American Jewish kids at school enjoyed Friday nights, but being Mizrahim from Iran, most of us had never heard of challah, anyway.

At first sight of my mother, everyone suddenly quieted down. The moment was too important; too part and parcel of our every being. Even “Full House” went to commercial break.

My mothers and my aunts recited the Hebrew prayer for lighting Shabbat candles; my father led the Kiddush and Hamotzi blessings over wine and bread. And that’s when I understood: We had escaped Iran, found temporary refuge in Italy, and were now living in America. And all throughout our journey, the only permanent identity we had consistently (and figuratively) carried on our backs was our Jewishness.

That’s what we were to the regime in Iran and that was why the U.S. government offered us protected (religious) refugee status: We were Jews, just like our Ashkenazi neighbors whose grandparents had escaped Poland in the 1930s, and the Jews who had been expelled from Spain and Portugal 500 years earlier, and the Russians with whom we had shared a small apartment back in Ladispoli.

In the years that followed, I left my parents’ apartment to attend college, where I befriended young American Jews who had never met a Jew from Iran (or Iraq, Yemen or Morocco, for that matter). As a campus pro-Israel advocate, I was called a “colonizer”; more recently, as a Jewish activist, I’ve been accused of being grossly “privileged.”

With every accusation, I find myself returning to those Iranian passports, which I keep at home. One still has a hole in the corner; the other still bears the word Kalimeh next to my mother’s name. And my mind vacillates between memories of beloved relatives in Iran whom I never saw again; of desperate searches for used mattresses on Italian streets; and of gloriously loud Shabbat dinners as free Jews in America.

There is one truth that I continue to embrace with sheer joy: Whether pita or challah, no matter how you slice it, I am eternally, unabashedly and irrevocably Jewish.