“They sent me to a gan called Simcha in Rechavia, a distance of half an hour’s walk from the house and I stayed there all day until four o’clock in the afternoon. The teacher was a yeke, a German who was very strict with us and whoever did not listen to her was punished. We ate lunch there daily that was a vegetable soup that was tasteless with no flavor and no smell. We were forced to eat this soup and whoever did not eat it willingly had it forced into him. There were children, like me, who were nauseated by this food and threw up. The teacher would take the throw up and put it back on a spoon after gathering it up from the table and feed it back to us while she screamed, ‘Open your mouth!’ For many of us lunchtime was a cruel nightmare, but what could be done?”

—Excerpt from one of my Abba’s letters, Jerusalem, British Mandate Palestine, 1939

(Originally published in White Zion by Gila Green, Cervena Barva Press, 2018)

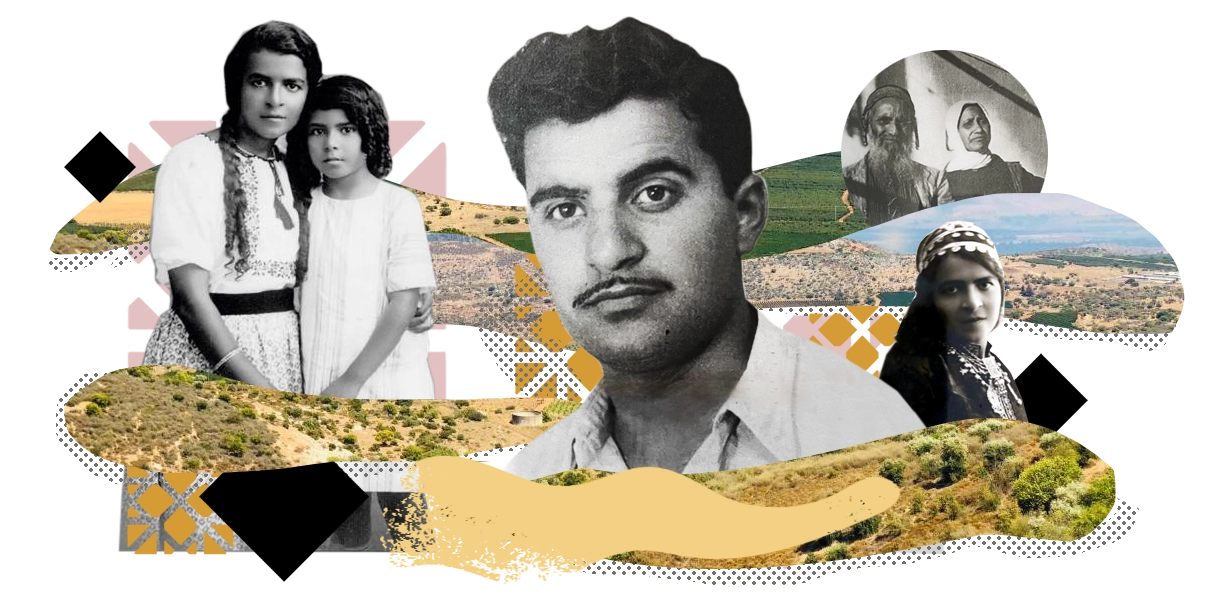

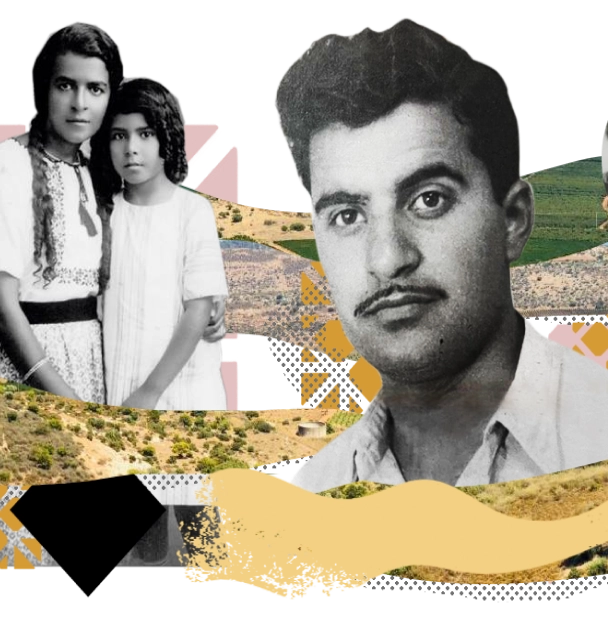

This is only one of the many anecdotes my Yemenite father told me about growing up in pre-State Israel. Always the villains in his stories were Ashkenazi Jews and he did not differentiate between males and females. To this day, I am gentle with my father when he narrates these stories. I know these are deeply ingrained experiences for him. He is galaxies away from listening to me explain how the new generation of Israelis sees the world, how I see the world; it is not his world after all.

Still, those narrated tales from his youth in Jerusalem painted vivid pictures and left indelible marks on my memory, shaping my perception of Israel. From the other side of the world in peaceful, polite, parochial Ottawa, my childhood imagination painted Israel as a cruel, primitive, war-torn place with constricted streets lined with jukim (cockroaches) and overheated leftovers that emitted a smell strong enough to turn your stomach. Consequently, I distanced myself from the notion of Israel.

Yet here I am living in the State of Israel, going on three decades now. During that time, many have asked about how I came to be here, expecting tales of Zionist passion, love for the land, or an affinity for its people, culture and religion. But none of that was true. My decision to move to Israel more closely resembles a movie script that might be called “Bridging the Divide” rather than “The Promised Path.”

After completing my third year in Carleton University’s Journalism program, with one left to go, a friend encouraged me to spend a year in Israel based on his own positive experience as a Canadian on a Tel Aviv University year-abroad program. He insisted that not only was Israel nothing like the country in my father’s memories, but that he had “found a place where everybody looked like me.”

As a half-Mizrahi, half-Ashkenazi Jew myself, the idea was intriguing. In Ottawa, I passed for anything and everything, asked daily if I was Italian, Greek, Lebanese, Iranian, or Pakistani. I was tired of my perpetual outsider status.

The beginning of the next school year found me in Haifa and later on a kibbutz where I met my future Johannesburg-born husband. Our relationship continued even after I returned to Ottawa to finish my degree and soon, he visited me on his first trip to Canada on a tourist visa. This was during the tail end of the Apartheid era when it was not easy for South Africans to travel. In immigration lines at the airport, he was asked to step aside and forced to endure interrogation. It was not much easier for me to spend extended time with him in South Africa, as the government there forbade me to work in my professional field: journalism. Publicity of any kind about the goings-on in South Africa, it turns out, wasn’t what they were looking for.

Our long-distance relationship endured and eventually we got engaged. We planned to live in Toronto and had tossed around the idea of moving to Israel “when we could afford it” so that neither one of us would feel like the guest in the other’s country. But we couldn’t have spent more than a few minutes discussing it — until one day when my telephone rang and my not-yet husband was sobbing on the other line, almost unable to speak.

“My visa was rejected,” he stammered. “They’re suspicious and they’re not letting me back in Canada.” As I was barred from working, South Africa effectively was closed to me. And now Canada was closed to him.

“Start the aliyah process,” I said. My future husband was taken aback.

“Aliyah?” he responded. He didn’t speak Hebrew, know anyone in Israel or come from a Zionist family.

“They’ll pay for your flight,” I said. “See you in a few months.” Four months later, Israel let both of us in — something we had learned not to take for granted.

While my initial journey to Israel defied expected narratives, my story since being here aligns with a more profound theme — unity. My international identity — Yemenite father who grew up in Jerusalem, Canadian mother from an Ashkenazi family, South African husband, Israeli children and their Sephardi spouses — represents a celebration of diverse experiences that shape who I am and who I aspire to be. These are experiences I only could have had by making aliyah some 30 years ago.

Today, I teach college students in Israel, my classes often comprising Sephardi, Ashkenazi and Ethiopian students from all corners of the country. When I share my mixed background with them, a palpable sense of ease ensues. This especially becomes evident when discussing their parents’ and grandparents’ aliyah stories, family recipes, vacations, and holiday customs. The exchange of perspectives and sharing of stories in my classroom affirms the significance of embracing our unique identities. Each semester, I witness firsthand how my varied background fosters meaningful connections with students, creating a space where they can freely learn.

The teaching experience has been only one of many instances in which I’ve recognized the beauty of my international mosaic at work. As I continue to navigate my path in Israel, I carry the classroom lesson with me as a reminder that my identity isn’t just a collection of origins; it’s a catalyst for making us who we are. Unity flourishes when people are given a platform to share their narratives and contribute to a greater understanding.

Similar feelings emerged when my daughter introduced her half-Moroccan, half-Argentinian fiancé; my son brought home his half-Yemenite, half-Turkish bride; and another daughter married into a family of South African new immigrants. Israel’s dynamic environment fosters my own growing family’s sense of belonging.

Though I still don’t fit into one slot, there is an element of an Israeli essence that has slowly become an inseparable part of me — this sense of belonging, which has allowed me to create a personal history with the land. It’s a connection I’ve rekindled and passed on to my Israel-born children, who are sharing that connection with my father in ways I never could.

I have learned that the beauty of life lies not in fitting into one slot, something I yearned for in my youth, but in celebrating the mosaic of experiences that make us who we are and who we are yet to become.

Note: The author wrote her original article in August 2023 and added new content in October 2023, after Hamas waged war in Israel. The new content begins here:

“The school was closed and no one went to work. Everyone was conscripted into the military or to help in the hospitals or to bury the dead. Across from the house, the dead were in crates piled one on top of the other. From the hill across from the house, all day we heard the screams and the cries of the parents and families from the nonstop funerals taking place. In daylight, there were the continuous sounds of the screaming and crying over the dead and, in the night, we would wake up to the shrieks from the mortars.”

—Excerpt from my Abba’s letter from when he was a 12-year old boy in Jerusalem, British Mandate Palestine/New State of Israel, 1948

I translated these words 18 years ago, and they rushed back to me on the second day of the October 2023 war in Israel. It goes without saying that I can cross out 1948 and write 2023 in its place. The meaning of this is apparent. We have arrived where we have already been. What was once is again. The grandchildren inhabit the spaces of their grandparents.

All of this is devastating and true. But there are other truths I want to share with you. It would be unjust to leave you with only this excerpt, with only these conclusions. It would be a disservice to how far we have come and against the Jewish idea of hope in the darkness for whom so many have already lost their lives.

Let us return to another of my father’s letters from the same moment in time:

“The situation worsened and we received coupons for food and water. I made a wagon with four wheels for olive picking in Emek Hamatsleva, the Valley of the Cross, and my mother also taught me to pick good plants to eat like kubezah and roots of various kinds. I went around the neighborhood with friends looking for food and collecting shells from bullets just for keepsakes.

In the night we would watch the mortars flying through the sky … every day we stood in line for our bucket of drinking water… the one in charge opened the lock and the cover of the water hole. There was a pail on a rope that we would throw into the water and fill up our bucket; life for the soul. The days were hard — no food and little water and no radio to listen to the news.”

In spite of stark similarities within these letters, Israel of 1948 is not Israel of 2023. (Do you hear me, Abba? Today, he is in his 88th year and in shock at what he feels is a return to his past. My protests go unheard, his ears too filled with anger and sadness to hear them.)

We have plenty of food and water — there are no coupons, there are no water holes or lines of people waiting in them. Today’s Israeli teenagers who are too young to serve or who are not currently conscripted do not have to build wagons and forage for food in nature. And as far as radio news goes, it is a struggle to keep them off of the endless news streaming into their eyes and hearts.

They are strong and they can do!

This week alone, my daughters have packed thousands (yes, thousands) of packages for soldiers containing everything from food to clothes to toothbrushes, from morning to night. They have been making tzitzit at soldiers’ requests, raising thousands of shekels online, babysitting for mothers whose husbands are in the army, creating activities to keep groups of younger children occupied, and probably another half-dozen things I don’t even know about.

They do not brag about it; they barely mention it in passing as they whiz out the door — again. No one had to ask them or tell them. They are indeed inhabiting the spaces of their grandparents, but this time with vast resources they intuitively know how to use.