I sit in an office in the East Bay of Northern California. There, in a room filled with iconography from the Far East, I hold a vibrating paddle in each hand and replay a traumatic experience in front of a therapist I barely know. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy aims to help people process traumatic memories, so I am doing what I can to recover from the intrusive thoughts taking over my life.

A few months prior, near the end of a trip to explore my family heritage in Tunisia, my 6-year-old daughter, Nava, and I survived the May 2023 terrorist attack at El Ghriba Synagogue on the island of Djerba. As I recount with my therapist the hours before the attack and the moments leading up to it, I can’t stop thinking about fish — the smell of fish, the image of fish, symbols of fish on walls, and thoughts of fish, and a story about fish from 26 years ago.

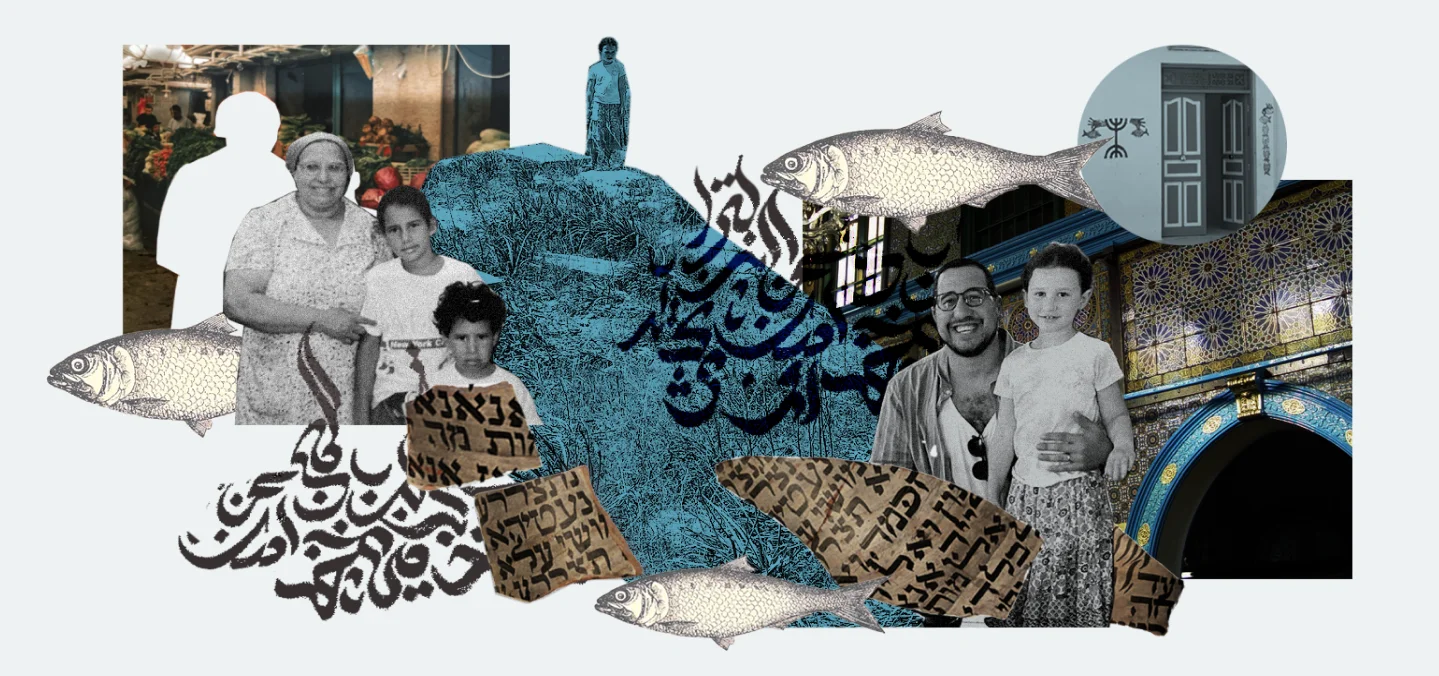

I grew up in Toronto but spent many summers visiting my mother’s parents, eight sisters and their families in Jerusalem. Her family fled Tunisia in 1967 after the Six-Day War when aggression against Jews forced thousands to leave their homeland. When visiting Jerusalem, we often slept in my grandparents’ one-bedroom apartment. My Safta Ruti loved to shop at Mahane Yehuda, the large outdoor market, and she took us there every few days. I suppose it reminded her of Nabeul, her birthplace, a small coastal town in Tunisia with a large open-air market in the center.

As a child, I loathed Mahane Yehuda. In those days, it was not the gentrified boutique market of today. Live fish and freshly slaughtered chickens filled the spaces between produce sellers. The sights and smells of poultry and fish nauseated me. On one particularly hot summer day, I had endured enough and begged my safta and mom to go home. Although Safta Ruti was not finished with her shopping, she had sympathy for me and we took the No. 4 bus back to her apartment.

As soon as we walked through the door, we saw my Saba Nissim watching news coverage of two suicide bombers who had blown themselves up minutes after we left the market. Sixteen people were killed in the market attack and hundreds were injured. I recall thinking proudly that the disgust I had for fish somehow had saved us, that I was the hero of our family story.

The morning of the attack at El Ghriba, Nava and I had walked through the souk in Djerba to get some last-minute gifts for our family as it was our last day in Tunisia. At some point, we entered the fish market. I looked at the freshly caught fish laying on large wooden tables, and I thought about that day 26 years ago in Mahane Yehuda. I dismissed the worry that this was an ominous sign. These fish didn’t disgust Nava; rather, she thought they looked interesting and amusing and posed for pictures with them.

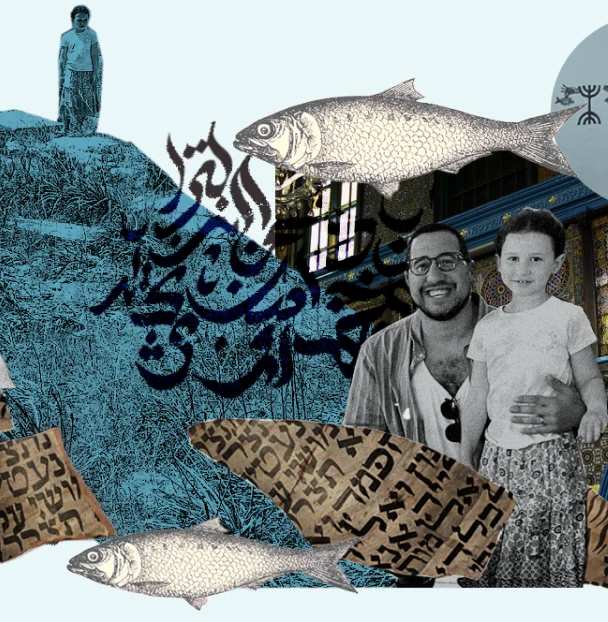

All photos courtesy of Adam Eilath

On most Jewish homes in Hara Kebira — the predominantly Jewish neighborhood in Djerba with 13 active synagogues, several kosher restaurants and Jewish schools — there are drawings of good-luck symbols on exterior walls. Most common among them is fish, or strings of fish. In Djerba, it is common for Jewish men and women to be named Hueta or Huetu, meaning “fish” in Judeo-Arabic. Nava’s intrigue felt like a tikkun — a repair of the fear I had dismissed in the souk.

* * *

During my trip to Tunisia in May 2023, my first and only, I met Natanel Bitane, a 25-year-old Jew who lives in Djerba. An artist, scribe and musical performer, he is one of the last 1,800 or so Jews who still live in Tunisia, which is one of the last Arab countries in the world with an active Jewish community.

I had traveled to Tunisia with the long-held dream of unraveling threads of my own identity. I am a Tunisian Jew by descent on my mother’s side. Her birthplace of Nabeul, an hour south of the capital city of Tunis, once boasted a Jewish population of 2,000, or half of the town’s entire population. Today, there are no Jews left in Nabeul and just a few of mostly elderly Jews in the capital of Tunis. After a few days of visiting Tunis and Nabeul, Nava and I spent the majority of our eight-day trip to Tunisia living with a Jewish family in Djerba’s Hara Kebira.

We met Natanel on a Friday morning in Hara Kebira, where his family has lived as far back as they can trace their roots on his father’s side. When I saw him, I instantly recognized him. Eight years ago, he and his classmates rose to fame through the subculture of online enthusiasts of piyyutim. Videos of him and his young friends reciting the Hebrew liturgical poems captured the hearts of Tunisian Jews who were heartened to see young Jews thriving in modern-day Tunisia, singing rare melodies and lyrics thought to be relegated to the archives.

Years later, Natanel reappeared online as an artist selected to participate in Djerbahood, a street art project, in the Hara Seghira neighborhood where El Ghriba is located. The graffiti and street art installations helped build the reputation of a tolerant, diverse and thriving culture that existed on the island of Djerba.

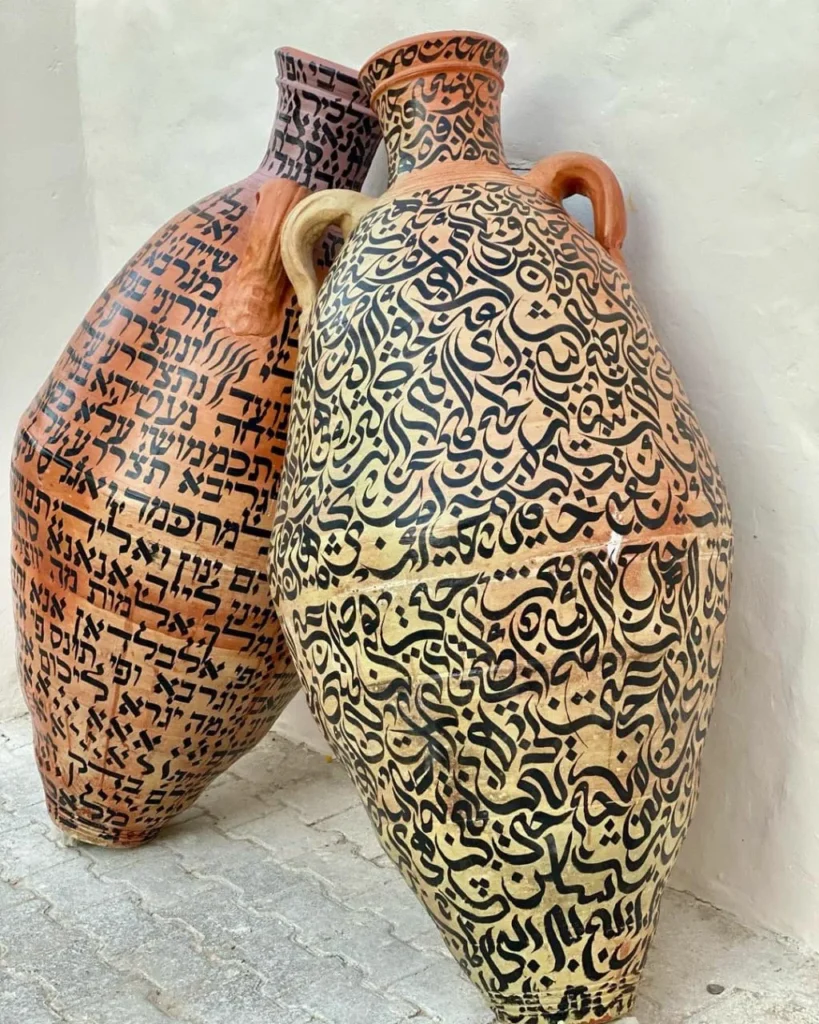

Natanel created his contribution to the exhibit in creative partnership with a local Muslim artist of Amazigh origins, the two of them scribing calligraphy on two large ancient-looking jugs that leaned against one another. On one jug, Natanel inscribed the words to a famous piyut about El Ghriba in Hebrew characters but in Judeo-Arabic language. His artistic partner inscribed on the other jug an ancient Amazigh poem about Djerba.

Natanel was one of the first Jews we met upon arriving in Djerba. I had asked our hosts if there were any synagogues still praying shaharit at that hour, when Natanel showed up at the door, also on his way to pray. My hosts introduced us and Natanel walked me and Nava through the winding streets of the hara, pointing out the schools, the synagogues, the kusha (the communal oven), and the art all over Jewish homes. I prayed shaharit with Natanel and then didn’t see him very much more on the remainder of my trip.

Our trip to the island was magical. The kindness, intensity, devotion and piety of the Jews of Djebra is unparalleled. Nava got to spend four days attending an upstart Jewish Day School for girls, Kanfei Yona, for which I had helped raise money over eight years ago. Nava was placed in a first-grade class with eight other girls. She sat among friendly and eager students who embraced her with hugs and smiles, which brought me tremendous joy. On Shabbat, I learned that Nava and some other girls caused a little mischief as they weaved in and out of Jewish homes in the neighborhood. I envied the ease with which Nava blended into the community. At one point during our stay, I heard her say to another girl, “ija” (Judeo-Arabic for “come here”). It felt like our visit was a tikkun — a repair of my family’s Tunisian story.

* * *

During our last two days in Tunisia, we spent our nights at the El Ghriba synagogue for the Lag BaOmer festival that brings thousands of Jews from across the world to Djerba every year. On the second night, Nava was playing with her friends in front of the buildings when a naval guard drove up to the synagogue and opened fire 100 feet from where she was standing, killing five. I wasn’t with Nava when the shooting started. I heard gunshots and screaming, and stood frozen while mothers, fathers and children frantically fled into hiding across the sprawling synagogue and adjacent foundouk (an inn or a hotel). It took 10 minutes for me to be reunited with Nava, 10 of the longest minutes of my life.

I learned later that Nava had been protected by French/Tunisian filmmaker Cléo Cohen, who grabbed her, along with another 6-year-old girl, and hid in a small room until I was able to reunite with Nava. After we were united, there were more gunshots and we fled into a dank, windowless, small room with Jews crammed shoulder to shoulder who were hiding, praying and desperate for salvation. Cléo has written powerfully about the experience for the French Jewish online magazine, K. There, she describes the many hours we hid and waited:

“The horror of the attack was the horror of waiting, literally, three-and-a-half hours of cold sweat, shaking, kids vomiting and pissing themselves, tears, pleading with our heads turned to the sky. Three hours and 30 minutes of imagining that death could appear just like that, unjustly, one blast and that would be the end of my tiny life, of our tiny lives. I think of our terrible helplessness.”

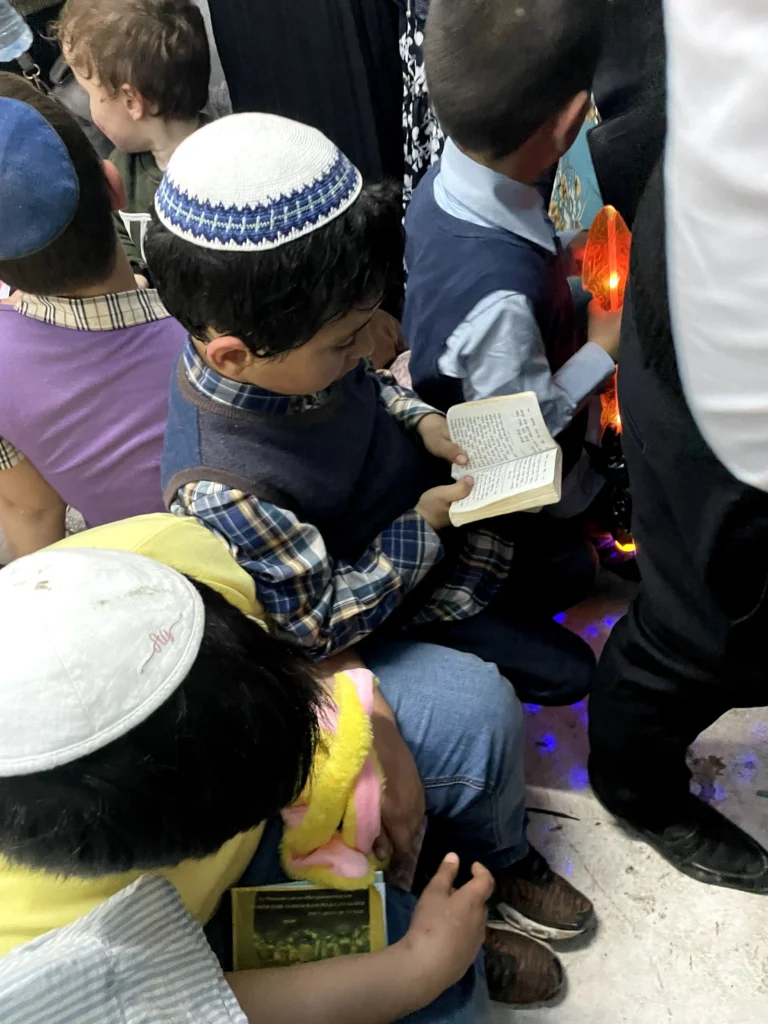

In that small room, adults hid the kids in the back, behind old mattresses, hopeful that if a shooter entered, the children would live through any injuries. In that room, boys as young as 6 feverishly recited Tehillim and adults displayed worry with just their eyes and their silence in a way I never had seen before. The hours we spent hiding reduced us to animals. Before, a student of Jewish history, I now was the subject of it. If before I experienced small repairs, this was a terrible rupture.

* * *

Nava and I were scheduled to leave Djerba a few hours after the attack on the synagogue. By the time we were evacuated, we had only a few hours to pack and get to the airport. We never were able to get closure with the community or spend time with the others with whom we hid on that terrible night.

One of the only members of the community who reached out to me to check in after the attack was Natanel Bitane. I had heard through my host family that he was very close to the shooting and escaped death by a matter of seconds. Natanel shared with me that he was still in shock from the attack and having a difficult time recovering. I was touched that he reached out to me, especially given all that he had endured.

Nearly nine months after the attack, Natanel and I arranged to talk about our experiences. He shared that as he was walking into the synagogue, he was stopped by several people who kept him in conversation. He believes that these delays were G-d watching out for him, for if he had not had just one of those conversations, he likely would have been among the victims of the attack. I shared with him my story of the fish and how I should have realized that our interactions in the souk that day were not a Tikkun but rather an ominous warning of what was to come.

Natanel, it turns out, also had dismissed a similar warning. He told me that two days before Purim, a few months before the Lag BaOmer attack, someone had come and shattered his jug art piece in the Djerba neighborhood. It was a heavy blow to him as an artist; he had spent weeks working on the installation and was proud of what he had accomplished. The jug beside him, inscribed in Arabic, was untouched.

I reflected on the words of the piyut written on the jug that Natanel had inscribed. The song is sung from the perspective of Serah, daughter of Asher, granddaughter of Jacob: “Baba Yacub Tlmali, Ml’ach El Mut Ma Yutzlali,” one stanza says. Translated from Judeo-Arabic it means: “My father Jacob told me, the angel of death won’t touch me.”

Natanel said that was his sign. “The two jugs side by side in Hebrew and Arabic were symbols of peace,” he told me. “The shattering of the Hebrew jug meant the shattering of peace. The song on the Hebrew jug represented a promise to protect El Ghriba and I understood after the attack that protection for El Ghriba was broken as well.” He shared photos with me of the broken shards of pottery speckled with his calligraphy. He lamented the destruction of his hard work and expressed sadness about the state of affairs in his community.

I thought about the way the Kabbalah describes the creation of the world, the breaking of the vessels via G-d’s infinite light. We are told that our life’s journey and goals should be to find those broken vessels in everything, in some of the darkest places in the world, and to bring them together for repair: Tikkun. I thought about Natanel’s shards of pottery and the shattered promises of protection, and I wondered if they would ever be repaired.

Students hiding during the terrorist attack in Djerba read Psalm 121 from the Book of Tehillim.