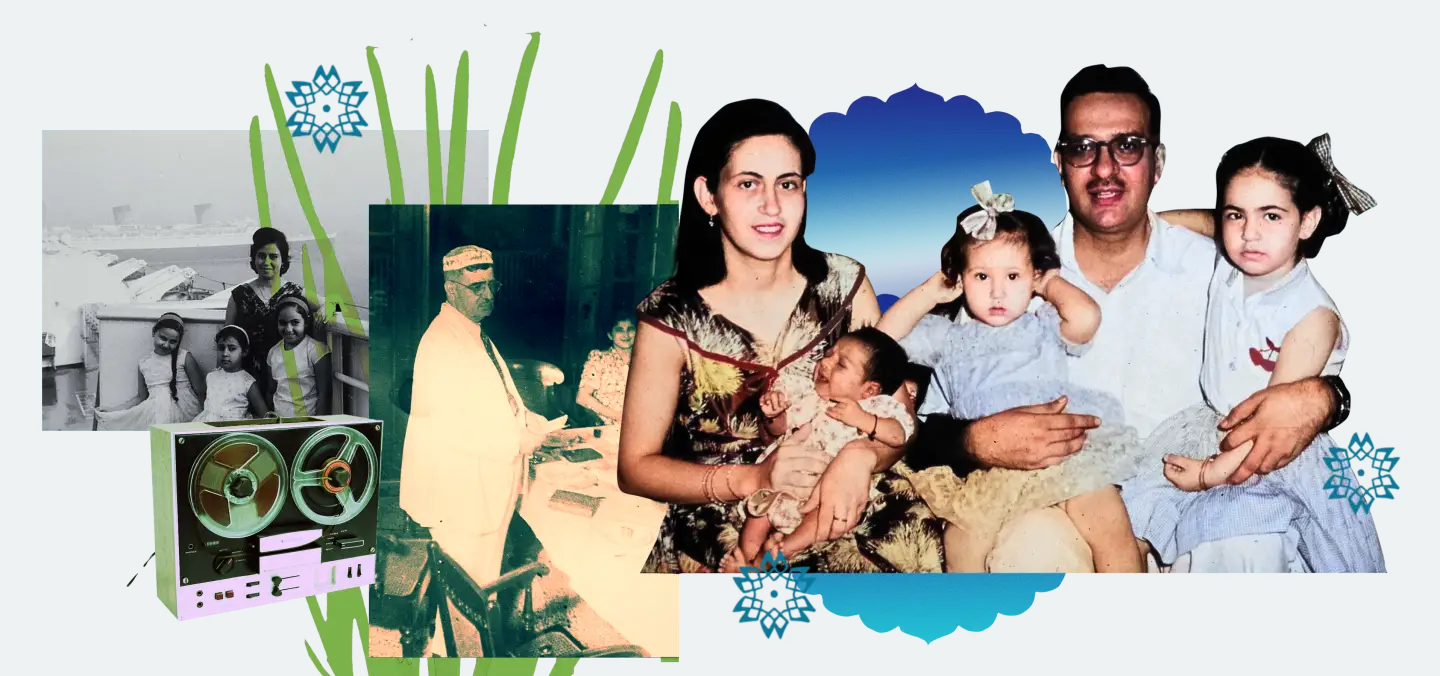

When I emigrated with my family from Calcutta to Philadelphia in 1964, nobody in our new city ever had heard of a Jew from India. I remember standing up in front of my second-grade class at the Solomon Schechter Day School singing the Indian national anthem, “Jana Gana Mana,” to prove that, yes, I really was a little Indian girl.

We had made the transatlantic journey by ship and docked in New York Harbor in late July. Rosh Hashanah was just over a month away and my father was busy preparing himself for his new role as rabbi of Mikveh Israel, the colonial Spanish and Portuguese synagogue in Philadelphia. He spent hours with a reel-to-reel tape player, learning the Sephardi melodies that differed from the familiar Calcutta chants that had roots in our Baghdadi tradition.

My mother had her own challenges. Having relied on our Indian cook in Calcutta, she had to navigate her new kitchen. One of her first tasks was to prepare the Rosh Hashanah seder. On the first night, Sephardi and Mizrahi families hold a special ceremony at home during which we recite blessings over a variety of foods that symbolize our wishes for the new year. This seder ritual is called yehi ratson (“may it be God’s will”) because we ask God to guide us and provide us with bounty, strength and peace in the year ahead.

The seder yehi ratson originates in the Talmud (Horayot 12a) in a discussion about symbols that carry significance. Rabbi Abaye suggests that at the beginning of each new year, we should partake of eating specific foods that grow in profusion and therefore represent prosperity.

For our first Rosh Hashanah seder the United States, my mother went shopping for sticky-sweet Medjool dates; apples that would be blush spicy pink when cooked into jammy maraba; ruby-red pomegranates; foot-long lubia beans; emerald-green saag (spinach); oniony lusson grass; and pumpkin (a pale gourd different from the orange variety we know in the U.S.). Her list even included a sheep’s head, which symbolizes that we should be heads and not tails — leaders, not followers.

Not surprisingly, she didn’t find everything she needed. Pomegranates and long beans were hardly staples in the 1964 American supermarket. And where do you find lusson grass? She settled on scallions as a substitute. According to family lore, she actually found the sheep’s head — or maybe the euphemistically named “sweetbreads” — at a kosher butcher, but knowing little about refrigeration, she left it out and it rotted.

The start of this new year also would symbolize the start of our new life in America, an early lesson for me in resilience.

Whatever we ate at that first Rosh Hashanah seder in our new home, the ritual itself was unchanging, comforting in its stability and order, guiding us toward optimism for the future. Then and every year thereafter, I would look forward to the seder yehi ratson.

This custom of announcing the exact beginning of the new year was an intimate moment for our family. ”

My father would always begin by reciting a series of biblical verses that carry mystical significance, each one relating to blessing, wholeness, light, and prosperity. He repeated each recitation 10, 12 or 17 times — 10 for the number of commandments, 12 for the number of tribes and 17 for the numerical value of the word tov (good).

I have always loved the grammatical construction of the last verse he recited: “V’atah shalom / u’vet’kha shalom / v’khol asher l’kha shalom.” In English: “You are peace / your home is peace / everything you have is peace.”

It’s not “You shall have peace” or “You are at peace.” It’s “You are peace.”

You embody peace.

After my father would chant this verse, he would pause and everyone around the table would stand up. Then he would transpose the key in which he was singing to a slightly higher pitch: “Tahel shanah u’virkhoteha!” he would proclaim. “May the year begin with its blessings!”

This custom of announcing the exact beginning of the new year was an intimate moment for our family. By modulating his voice, my father embodied the proclamation of a blessed new year as if he were a shofar himself. The dramatic specificity of the words, then and now, always sends shivers down my spine. This moment and no other will usher in a year — so the verse says — that unquestionably will bring blessings in its wake.

The words “Tahel shanah u’virkhoteha” are taken from a long piyyut, a liturgical poem called Ahot Ketanah that introduces the Rosh Hashanah evening service on the first night. Written by Abraham Hazan Girondi in 13th century Spain, it refers to Israel as a young daughter who prays to God to heal her sorrows. In the original, each of its many verses ends “Tikhleh shanah v’kileloteha,” or “May the year end with all its curses.” The final verse, however, ends “Tahel shanah u’virkhoteha,” turning curses into blessings. Whatever evils have challenged us in the past year, the new year is wrapped in blessing from its very start.

The seder yehi ratson is just one of many rituals — both Sephardi and Ashkenazi — that embody the concept of resilience. Whether the rituals teach resilience, or our resilience throughout centuries empowers the rituals, that’s up for debate. Perhaps they coexist.

In my experience, Sephardi rituals raise the concept of resilience to a more tangible level. The foods in the Rosh Hashanah seder become vessels for meaning, effective because their physicality goes beyond the cerebral. We absorb and ingest the foods. What each represents becomes a part of us.

First, the dates. “May it be Your will, God, that all enmity will end. May we date this new year with peace and happiness.” (The word for end, yitamu, sounds like tamar, the Hebrew word for date.) Second, the pomegranate. “May we be as full of mitsvot as the pomegranate is full of seeds.” Apples: “May it be Your will to renew for us a year as good and sweet as honey.” Long beans (lubia): “May it be Your will to increase our merits.” (The word for increase, yirbu, resembles another word for bean, rubia.) Pumpkin or gourd (k’ra or kara): “May it be Your will to guard us. Tear away all evil decrees against us as our merits are called before you.” (K’ra or kara resembles the Hebrew words for “tear” and “called.”) Spinach or beetroot leaves (selek): “May it be Your will to banish all the enemies who might beat us.” (Selek resembles the word for banish, yistalku.) Leeks or scallions (karti): “May it be Your will to cut off our enemies.” (Karti resembles yikartu, the word for “cut off.”)

Originally, the seder called for both a fish head to represent fertility and a sheep’s head to symbolize our wish to be leaders, not stragglers. In my family, we stopped using these last two items: the fish because its Hebrew name, dag, sounds too much like da’agah, the Hebrew word for worry. The sheep’s head, for obvious reasons. Today, I substitute cauliflower or a head of lettuce.

What does it mean to ask for a good, sweet year? I think it’s harmony and wholeness we are requesting — the ability to take the parts of our lives that may satisfy us disparately and put them together so that they create contentment. Through these simple foods, we ask for the ability to appreciate the basic goodness of our lives, the building blocks of resilience.

The Rosh Hashanah seder does not focus exclusively on sweet symbols, but rather it mirrors the realities of our lives. The bitter truths, fears and enmities with which we live mix with sweetness. Life is not just beginnings; it is also endings. It’s not just honeyed dates; it’s also the sting of scallions. It is about uncovering blessings despite the elusiveness of peace. That’s resilience.

I am not very good at enduring the bitterness. After I take the tiniest bit of scallion possible for the blessing, I wash away the unpleasant taste with the sweet apple jam and dates. Through this small act, I can increase the positive while asking to be shielded from the negative. Finding direction and beauty in our lives through the basic fruits of the earth allows us to push aside the chaos that clutters our days and to uncover the goodness and sweetness of time.

The annual cycle of holidays is rich with opportunities to remember our ancestors’ resilience, and therefore, to enhance our own. ”

The Rosh Hashanah blessings differ from secular New Year’s resolutions because we ask for God’s partnership in the process. Each wish begins with “Yehi ratson Adonai Elohenu v’Elohei Avotenu,” words that reflect a faith in a power greater than ourselves, God’s guidance enables us to rely on our own strengths.

Our liturgical ritual is another powerful mirror of our resilience. Et Sha’arei Ratzon, a haunting piyyut recited before the blowing of the shofar, written by Rabbi Judah Samuel Abbas of Fez in the 12th century, reimagines the story of the Akedah, the binding of Isaac. The blow-by-blow narrative of 13 stanzas, simultaneously tender and chilling, is as appropriate after October 7 as it has been throughout our history. The poet promises in God’s name: “Say to Zion that the time of her salvation has come.”

The annual cycle of holidays is rich with opportunities to remember our ancestors’ resilience, and therefore, to enhance our own. The Passover seder, for example, explicitly ritualizes our resilience from slavery to freedom. In Sephardi tradition, we embody this transition even further by personalizing that re-enactment during the seder.

In Baghdadi homes, we gather around the matsa and put our hands on it gently as we recite Ha Lakhma Anya with a particular emphasis: “THIS is the bread of affliction.” Moroccan Jews hold the seder tray high up and pass it over the heads of everyone at the table, proclaiming that they have left Egypt and are now free. When Tunisian Jews break the middle matsa, they say, “This is how God split the Red Sea.” Persian Jews beat each other lightly on the back and shoulders with bunches of scallions or leeks when they chant Dayenu, perhaps to symbolize the taskmaster’s whip.

The Bene Israel Jews of Bombay also raise the seder plate, its special two-handled design making it easy to grasp. They say, “Bivhilu yatsanu mi-Mitsrayim,” which means “In haste we left Egypt.” Everyone around the seder plate tries to touch it and if many people are present, those who can’t touch the plate try to touch the shoulders of the person who’s touching the plate.

The physical contact with the seder plate — even vicariously — contains a flowing energy that not only recalls their Israelite ancestry but the story of their resilience when they originally landed in India. According to Bene Israel tradition, their ancestors fled Hellenist persecution in the land of Israel around the time of the Maccabees and were shipwrecked off the coast of Bombay. Only seven couples survived. They settled in the villages along the coast and over the centuries, they lived peacefully among their Hindu neighbors. They forgot many of their customs and traditions, but they also remembered many vital ones that kept their Judaism alive. Above the lintels of their doorways, for instance, they placed a palm print that had been dipped in sheep’s blood. It was refreshed every Passover. This was their mezuzah, based on the lamb’s blood smeared on the Israelites’ doorposts before the exodus.

This ancient sign was also a symbol of courage that publicly declared their Judaism. It mirrors the small but critical distinction in the phrase that follows the words Bekhol dor vador (“In every generation”) in Sephardi and Ashkenazi Haggadah texts. The Sephardi text reads, “l’harot,” to show, to show everyone else, while the Ashkenazi text is “lir’ot,” to see, to see ourselves as having left Egypt. This grammatical distinction could signify that it’s not enough to see or feel internally as if we have left slavery behind. We also need to show it tangibly. In Egypt, the Israelites had to show who they were so they would be passed over — but they also could have perceived the command to smear blood on their doorposts as inviting destruction by the Egyptians. They had to make a choice, to remain mired in slavery or to plunge into the unknowns of freedom. How we navigate our choices is the crux of resilience.

Our Sephardi rituals — during Rosh Hashanah, Passover and other times throughout the year — ask God to open the gates of favor and grace, to help us uncover our resilience so we can look ahead to the future with both realism and optimism.