From the time I was very young, my parents always talked about leaving our home in the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan and moving to Israel or the United States. Every day, I woke up knowing that Samarkand, the ancient city where I was born, was not where I would finish college, get my first job, marry, build a family, or buy my own house.

In 1991, the year of the collapse of the Soviet Union, between 8,000 and 10,000 Bukharian Jewish families lived in Samarkand. Under the nearly 70 years of Soviet Communist rule, it was dangerous to perform Jewish rituals or celebrate Jewish lifecycle events in public as the regime cracked down on organized religion. The Bukharian community had to be resilient, adapting to the country’s political climate of the time. Its members maintained their traditions in very unique and secretive ways.

The Bukharian Jews of Central Asia date back to their exile from Jerusalem after the destruction of the first Temple in 586 BCE. Instead of returning to rebuild the second Temple, they continued eastward along the Silk Road and established the first Jewish settlements in the region of Merv (Turkmenistan) and Balkh (Afghanistan). Over the centuries, they have lived through the rule of various empires, including the Persians, Achaemenid, Mongols, and Shaybanid, often alongside other religions such as Zoroastrianism, Buddhism and, predominantly, Islam.

The freedom to practice Judaism freely in Uzbekistan has depended on which regime held power.

Bukharian Jews are a Mizrahi community that adopted Sephardic customs in 1795, when Moroccan Rabbi Joseph Maman Maghribi settled there. At the time, the Bukharan Emirate was under the jurisdiction of the Umar caliphate and its discriminatory laws that granted Jews (and Christians) limited religious liberty only in exchange for payment of a jizya tax. Devastated by the act, community members searched for a rabbi to lead them through this dark period, and Rabbi Maghribi accepted their invitation with the understanding that since his practice was rooted in Sephardic tradition, the community would need to follow. The Umar caliphate’s oppressive laws stayed in effect through 1865, when Tsarist Russia began to conquer the land, although remnants of those laws persisted in some parts of the region as late as 1920. Under the rule of Tsarist Russia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Bukharian Jews were granted more rights, which benefited their trading businesses. That golden age ended abruptly, however, when the Soviet Union took hold in Central Asia in 1924.

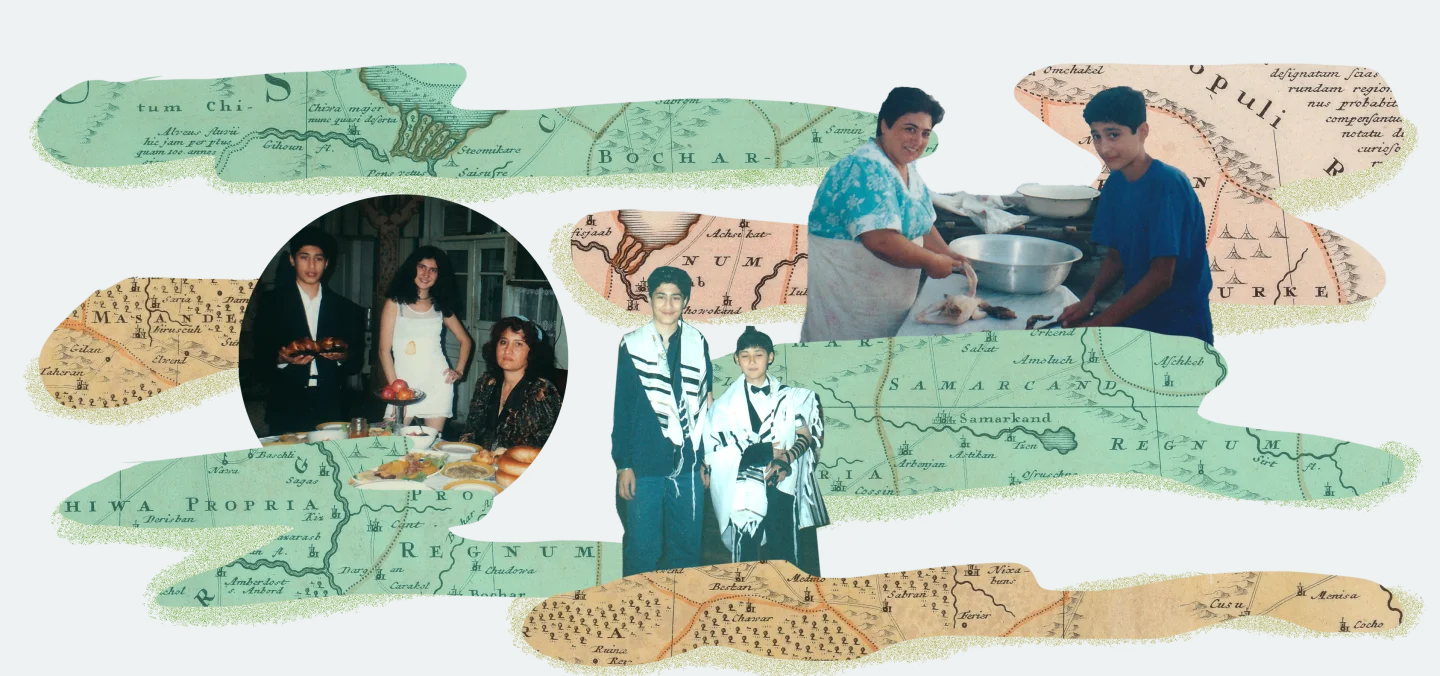

During the Soviet period, communal bar mitzvahs had to be held in lieu of individual ones, and sometimes the boys were older than 13. For example, among my father and his four brothers, only the youngest had an individual bar mitzvah. The other four brothers, including my father, had theirs together, beyond their 13th birthdays.

Communal bar mitzvah ceremonies took place very early in the morning because they required discretion and privacy. Each boy would be called to the Torah in the synagogue wearing tefillin, and the rabbi would read from the Torah, as the boys rarely did so themselves. That same week, during the memorial event yushvo, where families gathered in a courtyard to mark the anniversary of a loved one’s death, the rabbi or the oldest man present would announce the names of the bar mitzvah boys who had now become men.

These practices were organized in response to the hardships of living under Soviet rule, but nevertheless helped the community to persevere and survive.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, it became customary to travel to Israel and hold bar mitzvahs in Jerusalem at the Kotel — the Western Wall. Although it once again was safe to celebrate Jewish ceremonies openly in Uzbekistan, community members felt that with the newly opened borders, it made more sense for bar mitzvahs to take place on holy land.

He saw a community that questioned the survival of the Bukharian Jewish identity they had nurtured and helped to preserve. ”

My parents, Abrash Khaimov and Marina Borukhova, decided that we also would go to Jerusalem to celebrate my bar mitzvah in September 2000, when I turned 13. The tickets were booked, the restaurant was ready and people were invited.

One Monday morning, in preparation for my bar mitzvah in Jerusalem, my father took me to the synagogue in Samarkand for the Shaharit prayer. At that time, only about 170 Bukharian Jewish families remained in the city, as many had made aliyah in Israel or immigrated to the U.S. The morning service brought together mostly older community members who never could imagine leaving Samarkand. They wanted to die in the same place where they were born and where their parents were buried.

As they prayed, my father saw something deep within their hopeless eyes — something that even today I cannot fully grasp.

He saw a fear among elders who did not know what the future held for Samarkand given the exodus of families. He saw their worry of not knowing what would become of their loved ones who already had emigrated from Uzbekistan. He saw a community that questioned the survival of the Bukharian Jewish identity they had nurtured and helped to preserve.

After returning from synagogue, my father marched into our house and told my mother, to my surprise, that we were not going to Israel for my bar mitzvah. We were going to have it right here, in Samarkand.

And so, in the old city’s Mahalla Jewish Quarter Bukharian synagogue that was over one century old at the time, the first public bar mitzvah was held in eight years, followed by a celebration later in the Soviet-era Hotel Intourist, the only inn in town. I remember how the whole community, Jews and Muslims, came together to help our family prepare for the occasion. In Uzbekistan, there was no kosher restaurant or kosher catering, so we had to do it all by ourselves. We slaughtered the chickens, cleaned the fish and sliced the vegetables. We borrowed place settings from the two synagogues.

All the Jewish families that lived in Samarkand at that time were invited to the celebration of my bar mitzvah. To this day, I remember the bright faces of the community members in attendance. As I now reflect on my parents’ decision to hold my bar mitzvah in Samarkand rather than in Israel, I value it as a profound act that brought hope to the Jewish community in Samarkand.

The Bukharian Jewish community still exists today in Samarkand, although small in number. My family ultimately took part in the exodus out of the city despite my parents’ good deed and good will toward the community. Throughout my parents’ lives and my childhood, we always experienced some form of antisemitism, whether it was my father being denied entrance to university despite his good grades or in my own classrooms at school. As my two older sisters entered their late teens, my parents realized the best way to preserve our Jewishness as a family was — still — to leave Samarkand. Therefore, in 2001, one year after my bar mitzvah, we immigrated to the U.S., resettled in Brooklyn and eventually made our home in Queens.

Our community’s ability to adapt, thrive and remain steadfast in our beliefs tells a powerful narrative of our survival and triumph. ”

Unlike my father, I was accepted into university, attending Baruch College, where I served as president of Hillel and later received my master’s in community organizing, planning and development from Hunter College. Today, I am the founder of the Sephardic American Mizrahi Initiative (SAMi), an organization currently operating on 10 college campuses that serves as a mobilizing hub for Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews on college campuses nationwide. The same spirit of resilience that sustained the Bukharian Jews in Samarkand is demonstrated today among Sephardic and Mizrahi college students who have formed campus organizations and advocated for Israel, ensuring that their Sephardic and Mizrahi identity is not only preserved but also celebrated.

The day after October 7, when Hamas brutally attacked, kidnapped and raped civilians in Israel and organized terror for many families in Israel, SAMi sent an email to the students on our mailing list telling them that all the requirements they had to do for the semester could be put on pause and that we were here for them as a resource. Almost immediately we received a large number of replies requesting our help in hosting support groups on campus and in planning and organizing educational events around Israel.

Whether in the face of oppression from ruling empires or modern-day challenges of anti-Israel sentiments that have created hostile campus environments, our community’s ability to adapt, thrive and remain steadfast in our beliefs tells a powerful narrative of our survival and triumph.

When I started SAMi, its mission was to cultivate and advance Sephardic and Mizrahi American college students and young professionals to create and develop a pipeline of diverse leaders for the future of American Jewish peoplehood. What we have come to realize is that when Israel is at war, Jewish students on college campuses also are in a battle and face unprecedented threats.

Our Sephardic and Mizrahi traditions — demonstrated throughout our history — play a crucial role in building resilience. From a young age, we are taught the importance of family, Torah, community, and rituals. These elements are the bedrock of our identity, giving us the strength to withstand and overcome. My own experience, from my childhood in Samarkand to my life in America, has been shaped by these values, driving my commitment to teach and preserve Sephardic and Mizrahi identity for future generations.

My parents’ actions have demonstrated true leadership and shown the importance of unity. Their decisions inform my commitment to the preservation of the Jewish community, locally and on college campuses nationwide. They have instilled in me the idea of honoring our past so that we can pave the way for a vibrant and resilient Jewish community for generations to come.

Our sages say that all people should find role models in life to guide them. I am grateful to have found mine.