The Jewish Idea was born in the so-called “Middle East,” and so were the first people associated with that idea — the Children of Israel, later known as the Hebrews, or the Jews. In spite of thousands of years of migrations and dispersion all over the globe, the DNA of many, if not a majority of contemporary Jews still carries the markers of those ancient Middle Eastern origins.

Long-term history brought about stages of growing separation and differentiation, and stages of encounter and increasing convergence for the descendants of that initial tiny group of people. Many more people voluntarily joined the early Jewish tribal collective and the eventually more complex Jewish peoplehood. Probably many more severed their ties with Judaism and were lost along the way, often under duress. These contrasting identification patterns of continuity and change shaped the world’s Jewish population under a great variety of geographical, political, social, economic, cultural, and religious contexts.

The great amount of geographical mobility and mutual communication, which always prevailed between the different parts of the collective, helped keep a substantial common ideal thread across distant Jewish communities. But Jewish communities that experienced separated lives during long periods of time in different continents developed somewhat different genealogical trees, family habits, minhagim (customs), and nusahim (forms of prayer). One paradigmatic partition was the development of a Talmud Bavli and a Talmud Yerushalmi as two parallel bodies of Jewish knowledge and hermeneutics. In the sociology and semantics of Jewish discourse, the distinction became customary between Sephardi (Spanish) and Ashkenazi (German) Jews. These broad partitions relied on rough geographical criteria, and perhaps even more on family traditions and personal feelings. Real life, of course, unfolds mostly locally, and Jewish communities could be (and still can be) distinguished based on that micro-geography.

It is hard to pinpoint exactly when the term Mizrahi gained traction and popularity to designate the imagined East-West divide of global Jewry. In his famous medieval poem, Yehuda ha-Levi lamented: “Libbi be-mizrach ve-anochi be-sof hama’arav” (“My heart is in the East and I am at the edge of the West”), alluding to his being in Spain while his aspiration was to ascend to the Holy Land of Israel. The sentiment of ha-Levi was sincere, but the question of where East and West stand on a rounded shape body like planet Earth is pure fallacy. Every point on the globe stands at the East of one point and at the West of another.

The attribution of Mizrahi (Oriental) — theoretically symmetrical and opposed to Ma’aravi (Occidental) — to designate different Jewish communities, reflected a misfortunate hierarchical concept, not free from colonial and racist infiltrations. The West, and in particular Western Europe, long has been the locus of what one conventionally calls enlightenment, modernization and civilizational progress — in short, the ideal paradigm to be adopted for self and others in an emerging ideal world. The East, therefore, was perceived as the non-West, the other thing, the alternative, the less perfect paradigm that could benefit from the fruitful inputs of the West.

Intriguingly, these categories became frequently adopted in the description and classification of Jewish communities by completely neglecting the real geographical and spurious underlying meaning of these categories. Thus, Jewish communities of the North African Maghreb (by literal definition: West) became part of the definition of Mizrahi Jews. The collective caption Sephardim and Edot Hamizrach (Spanish and Oriental communities) collapsed together the Jews of ha-Levi’s “edge of the West” with those of the East. The putative counterpart, Western Jewish communities, actually was meant to designate Jews of European origin, including the more ancient communities of Western Europe (also known in German as Westjuden) and the majority of communities of Eastern Europe (also known as Östjuden). The confusion between East and West — in part fueled by the rhetoric of contemporary political discourse — could not be greater.

A less-biased criterion for the classification of Jewish communities would refer to the non-Jewish environment that predominated, whether Christian or Muslim. Such distinction was not trivial, as Jewish communities did maintain frequent exchanges with the surrounding society and to some extent were influenced by their laws, social norms and — significantly — economic development. A quick reassessment of the old world’s Jewish global presence, allowing for a virtual line on a map separating the Christian and Islamic civilizations in the past, would connect (for example) Tangier at the extreme West with Astrakhan at the extreme East. Such a partition would be roughly North-South, certainly not East-West. Interestingly, the Balkans, with its important presence of Ladino-speaking Jewish communities (as well as the most ancient Jewish presence in Southern Italy), would appear on the Southern side of that virtual map.

Should the southern Jewish community of Ethiopia, with its Christian environment, be included in this binary typology? Then, a more neutral mode of addressing different Jewish communities by their geographical and socio-cultural background would be the one adopted by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics: Asia and Africa; Europe and America. It is important to keep in mind that all binary classifications miss the crucial element of contiguity and gradualism that characterized the Jewish Diaspora. But to some extent they may be useful to simplify the description of a far more complex reality — which does not detract from the authenticity, resilience and relevance of particular sub-ethnic Jewish identities, no matter how defined, in Israel and transnationally across the world. The richness and autonomy of the many local and micro-regional Jewish cultures cannot be superseded by rough categorizations, and it actually shows through the revival of the study of local and regional Jewish languages, histories and customs.

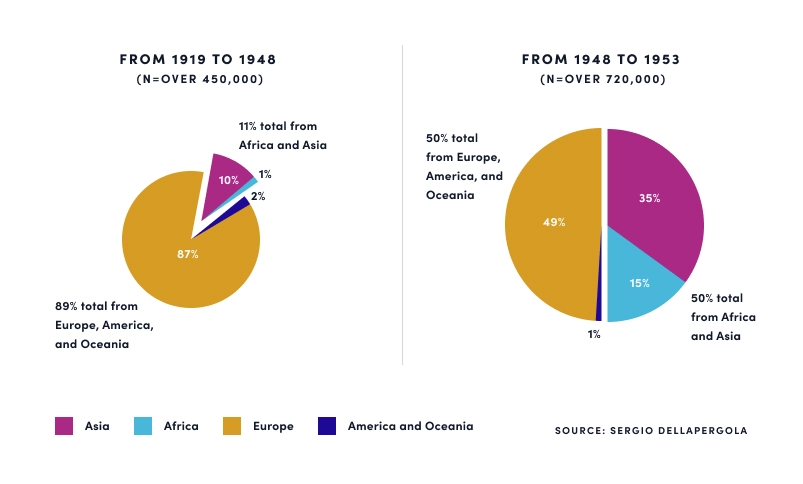

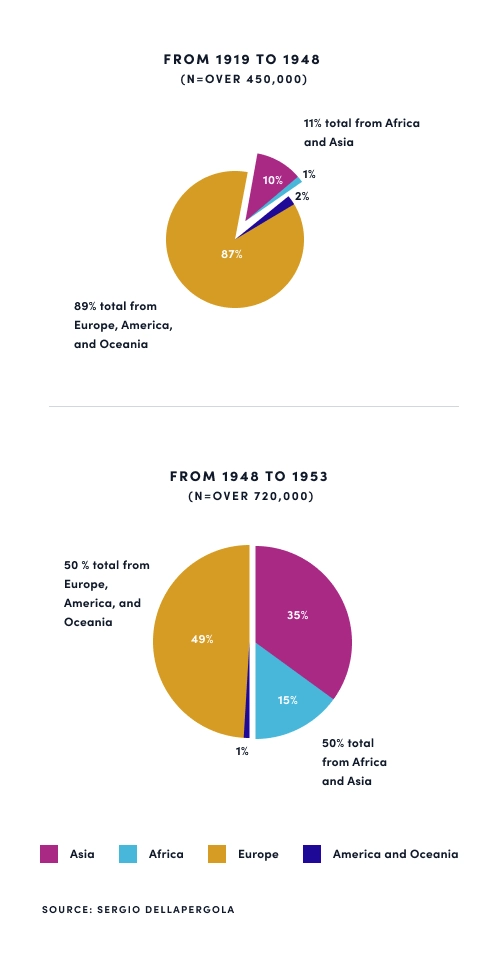

Immigrants to Israel: REGIONS OF ORIGIN

The trajectory of Jews from Asia and Africa who immigrated to the new State of Israel between 1948 and 1953 was influenced greatly by the Jews originating from Europe who had immigrated to the Land of Israel earlier in the century (1919 to 1948) and already had established social, occupational and geographic hierarchies.

The Zionist movement and the State of Israel, following the utopia of the Ingathering of the Exiles, created a large and heterogeneous immigration — hence, a renewed encounter — of Jews from all countries of the world. These Jewish immigrants, together with the pre-existing residents of the Land of Israel (yishuv), brought into the new settlement the diversity they had accumulated over many generations and centuries of separation.

The immigration to the Land of Israel that occurred decades prior to the formation of the State of Israel was crucial in influencing everything that has happened thereafter. During the era of British Mandate over Palestine, over 450,000 Jews registered as immigrants between 1919 and 1948. Of those, 87% arrived from Europe, compared to only 10% from Asia, 2% from America and Oceania, and 1% from Africa. Therefore, the human capital that created the initial cultural and socioeconomic profile — as well as the political orientations — of the yishuv and the emerging State of Israel was mostly of European origins.

The composition of the first mass immigration wave to the State of Israel was totally different, however. Among the over 720,000 who immigrated between 1948 and 1953, 35% arrived from Asia and 15% from Africa, along with 49% from Europe and 1% from America and Oceania — an even split with actually a decimal-point majority among the immigrants from Asia and Africa.

The initial absorption of these new immigrants was much affected by the veteran cadre already there. The first settlement of immigrants from Asia and Africa were dictated to live in the peripheral and less developed areas of Israel, where new towns and agricultural settlements were being created. Those who could settle in the larger and more central cities were more often European Jews, who therefore enjoyed since the beginning marked advantages in the quality of employment, services and social networks.

It also is crucial to keep in mind that Jewish immigrants to Israel reflected the socioeconomic and cultural conditions of the environments from where they came. Among Jews living in Western countries (Europe), the birth rate was already low in the 1930s, assimilation was high and life expectancy was far higher than among the non-Jewish population. By contrast in the late 1940s, Jews in Yemen, for example, experienced very closely-knit Jewish families and communities. Their isolation helped to keep pristine Jewish traditions, but the community also suffered an infant mortality rate of 50%.

Beginning in the 1950s, new immigrants in Israel from different backgrounds experienced an extraordinary process of demographic convergence. Community hygiene and sanitation gaps were drastically reduced through diffused improvements for all. Gaps in the Jewish birth rate of Sephardim and Ashkenazim tended to recede over time, and completely disappeared among the first generation born in the country. Fertility gaps by religiosity persisted across origin groups. Intermarriages across Jewish communities gradually increased, reflecting the ideal of the Fusion of the Diasporas but also the diminishing social gaps between the communities of origin. Most marriages tended to occur within the same social environment in terms of levels of education attained, but also religiosity of partners. Over time, the respective weight of the Jewish populations from the two major origin groups (Asia/Africa and Europe/America) became quite balanced in Israel.

The question of where East and West stand on a rounded shape body like planet Earth is pure fallacy. Every point on the globe stands at the East of one point and at the West of another. ”

Importantly, the socioeconomic characteristics of Jewish migrants tended to correspond to their choice country of destination. Such destination comparisons are necessary to analyze in order to put the history of aliyah absorption in appropriate perspective. In the late 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s in particular, significant educational and occupational differences emerged among the Jewish migrants who chose to go to Israel versus those who ended up in Western Countries, such as France. Israel absorbed fewer highly educated migrants with professional or managerial backgrounds, and instead drew in more semi-skilled and unskilled workers in blue-collar industries, the service sector and agriculture. Israel also attracted higher percentages of children and elders than did Western countries, resulting in much heavier dependency rates.

The more problematic fact was that socioeconomic differences between Eastern European and Mizrahi Jews who migrated to Israel were much smaller than the differences between migrants from Asia and Africa who split between Israel and the West. Therefore, the widening socioeconomic differences that emerged between Jews from different continental origins during the subsequent integration in Israel were the result of factors operating in Israel, not abroad.

Clearly, the Jewish migrants to the State of Israel, no matter their regions of origin, had lower occupational skills and socio-economic status than the Jews already established there — not to mention lower seniority in the country, both as individuals and as immigrant communities. Therefore, the absorption of the new immigrants was tougher in Israel than in the Western countries, where those gaps were less pronounced.

A notable process of downward mobility was shared among the new immigrants. The starting points for immigrants originating from Asia or Africa actually were somewhat lower compared to those who arrived from Europe or America, and as a result, it should be acknowledged that the price the Asian and African immigrants paid in the first years for their adaptation in Israel was much heavier. They suffered a much more significant initial loss of social status than European and American immigrants, as they were less able to keep the socioeconomic positions they held abroad before migration and had to relocate at lower levels of the social ladder. Therefore, during the first absorption period in the State of Israel, the gaps that already existed abroad between the various groups of origin much deepened to the disadvantage of those from Asia and Africa. With this, sediments of bitterness were created in Israel, which would not be forgotten in the following decades.

What followed — gradually but consistently — was significant upward mobility, eventually reducing the achievement differences in educational levels, occupational stratification and income of the various origin groups, along with the already noted demographic convergence. Starting with the late 1960s, an intense process of upward occupational promotion emerged in Israel, with a parallel social rise of the two main origin groups. The percentage of those with academic and technical skills steadily increased among all origin groups. The percentage of laborers and agricultural workers decreased steadily and reached similarly low percentages among all origin groups, also reflecting some substitution at the lower social levels by Palestinians and later by foreign workers.

To fully emphasize the social significance of such occupational catch-up, one must compare the data for those born abroad and those born in Israel of the same origin. The occupational/social-class gaps narrowed much, especially as measured by the ratio between the two origin groups at the top level of the ladder, but gaps did not disappear in the second generation. To demonstrate: In 2021, the rate of persons employed in jobs requiring at least partial academic studies was 36% among those born in Asia or Africa versus 58% among those born in Europe or America, a gap of 22%. Among the second generation (those born in Israel whose father was born in Asia or Africa), the same percentages were 57%, compared to 71% for those born in Israel whose father was born in Europe or America — a gap of 14%. The gap was not only narrower, but at a far better occupational profile. The crossover point when the majority of immigrants and their children shifted from lower to higher status jobs occurred in the 1980s among immigrants of Europe or America origin, and around 2010 among those of Asia or Africa origin. More time — at least one more generation — still is needed for social class equalization to be completely attained, along with further blurring of origin boundaries through continuing intermarriages.

Another analytic angle is offered by examining the role and composition of the elites in Israeli society. Jews from Asia or Africa were able to achieve a visible presence — although not yet always the exact proportionality — in all avenues of the leading strata in Israel, with only two remarkable exceptions: As of 2023, no representative of the origin group yet had been prime minister or president of the Supreme Court. All other possible targets of a fair representation were achieved, including the presidency of the state, the top economic elites, the military, academia, in the Knesset, in the local authorities, in the trade unions, in the popular performing arts, and among outstanding athletes.

The political party system, however, continues to reflect the still-not-fully homogeneous social stratification and geographical distribution of major origin groups across the state, resulting in a stronger visibility of Asian or African voters and party regulars in the right-wing Likud than in the center or center-left parties. The sub-ethnically segregated Shas party was the counterpart of the equally sub-ethnically but also religiously segregated Yahadut Hatorah. Aggressive ethnic politics indeed facilitated achieving a share of power. As such, both gained a negotiation weight considerably heavier than their electoral strength, but also promoted a spiraling mechanism of preserving pockets of ethnic isolation, poverty and political party dependency.

The main mechanism of social mobility and promotion in Israel has been influenced by time and seniority in the country. The starting point for Jewish immigrants of Asian or African origin was later, and therefore weaker than that of others. Considering the recency of Israel statehood, the advancement of the country has been quite unique and impressive — from a poor ingathering of derelict immigrants without resources to one of 20 countries in the world with the highest Index of Human Development. The road undergone and the achievements by Jews who came from the poorer countries of Asia or Africa do not fall behind and in fact surpass any or all other international realities characterized by intense immigration and internal ethno-religious diversity.

Note: The author conceived and wrote this article in August and September 2023, prior to Hamas waging war in Israel.